Conjuring Images when Writing for Comics, Prose, and the Screen

by Jessica Maison

A writer conjures images for their readers, whether writing prose, film, or comics. Comics writing has a set of best practices that share similarities and differences with screenwriting and prose writing. Most successful stories told in any medium must establish a dynamic world and protagonist while presenting an enticing inciting incident, climax, and resolution. They must create compelling characters with relatable strengths and weaknesses driven by interesting motivations. However, distinct differences exist between these mediums. Writing for comics is a visual medium, as is screenwriting, whereas prose is a language-based medium. Yet all three need to conjure images and dynamically travel through space and time. The way a writer in each medium achieves those feats is where the nuances in the writing techniques exist.

Similar to screenwriting, most of the words a comics writer puts into a script are meant for the writer’s collaborators. The comics writer is creating a world for their editor, penciler, inker, colorist, and letterer. Indirectly, the reader will see a visual interpretation of the writer’s words by that team as illustrated in panels. Directly, the reader will experience the writer’s words in the captions and word balloons, mostly as dialogue. Because comics is a visual medium, the less dialogue the better is a good rule. In a visual medium, the story should be told primarily through images. The writer must decide what images are shown and what ones are not, and there is great complexity in those choices, especially in comics, where such limited space exists to develop the story. If done well, the team of artists will build a compelling world and characters using the writer’s well-crafted blueprint.

Screenwriters use scenes to break up their story, choosing when to cut in and out of scenes and manipulating time to create the flow for their story. In film, each frame is projected on the same space. In comics, each panel (frame) occupies its own space. The writer determines what is shown in those panels, creating an illusion of motion or suspense. Even the page turn plays a significant role in the comic’s pacing. A comics writer must consider what action will be on a spread and what will turn the page. Comics rely on readers to fill in the blanks to make their series of images feel fluid and exciting. The comics writer must guide how the reader fills in those blanks by what they show in the panels and when they show it. A writer and artist create a kind of magic when determining the number of panels to use, what images to put in those panels, and how to place them on the page.

Page from Ambitious Failures, Richard Fairgray’s graphic memoir.

Alternately, prose writers use only words, relying on their readers’ imagination to transform those words into images. The prose writer can do this with as many words or as few as they desire. They usually spend more time describing the setting, characters, and actions because they do not have a camera or an illustrator to create those images. The prose writer must use the reader’s imagination as the conduit to create visuals.

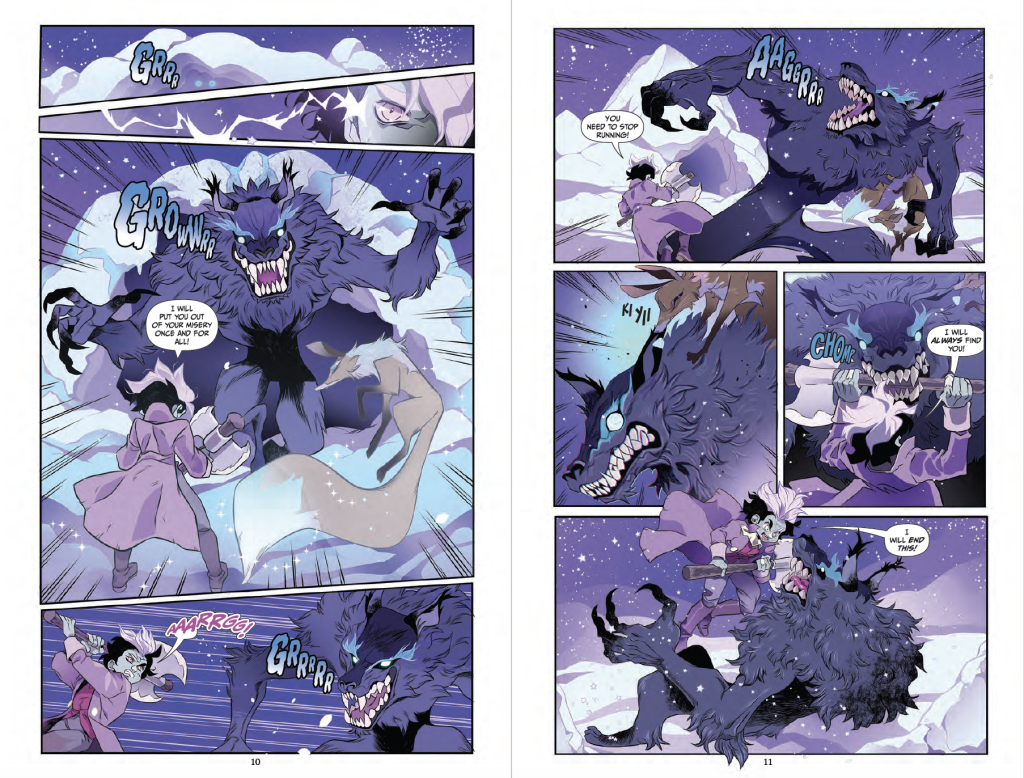

Pages from Mary Shelley’s School for Monsters: The Killing Stone, written by Jessica Maison and illustrated by Anna Wieszczyk.

A fight scene demonstrates the differences in the three mediums very well. In prose, expressing the character’s internal struggle is just as important as describing the external action in a fight. In film, the writer focuses on what actions the director, designers, and actors need to focus on to advance character and plot. The screenwriter must reveal the character’s internal struggle with key moments in the action or pieces of dialogue to develop the story further. Both in film and prose, much of the action can be shown or described. For a comic writer, there is limited space and no actual motion. The writer can’t show the whole fight scene. They must plan out frames and create movement through the actions they choose to reveal.

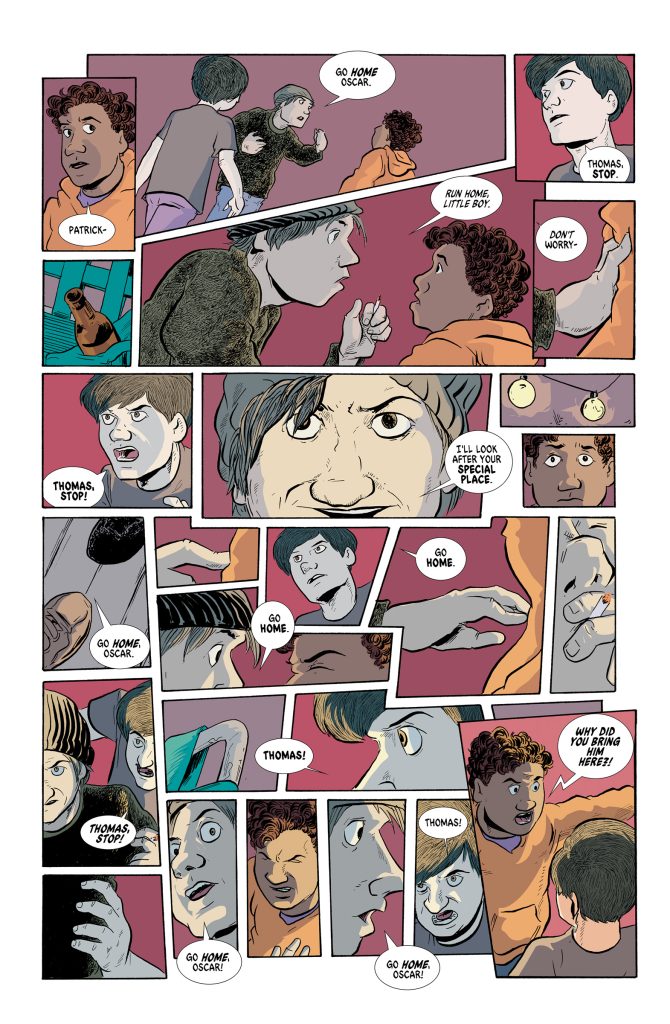

Page from the GLAAD Award-winning graphic novel Four Color Heroes by Richard Fairgray, published by Fanbase Press.

Page from the GLAAD Award-winning graphic novel Four Color Heroes by Richard Fairgray, published by Fanbase Press.

Additionally, a prose writer has more freedom to capture the abstract and invisible than a comics writer. They can take as much time as they want describing these things. In comics, a writer must show a character’s internal struggles using visual images and dialogue. Every emotion or motivation must be revealed in limited space and time. They can use thought balloons but sparingly. It is stronger to convey a character’s thoughts through action. That rule is valid in all mediums but is most crucial in comics.

The way the reader experiences time is different in comics than in novels and in films. A reader processes a comic in many parts all at once. They can see what is happening on the next page, catch glimpses of several dialogue balloons ahead, and continue to see the panels they just read. They aren’t just reading in the present like a novel reader, but also in the near present and recent past. The writer needs to keep that in mind when planning out each page and then each panel. A reader takes in more images at once than it does sentences, and that truth differentiates the approach for a comics writer from a prose writer and even a screenwriter. The way the comics reader experiences space and time is a constraint that, when utilized properly, advances a story in a way that can’t be accomplished in other mediums.

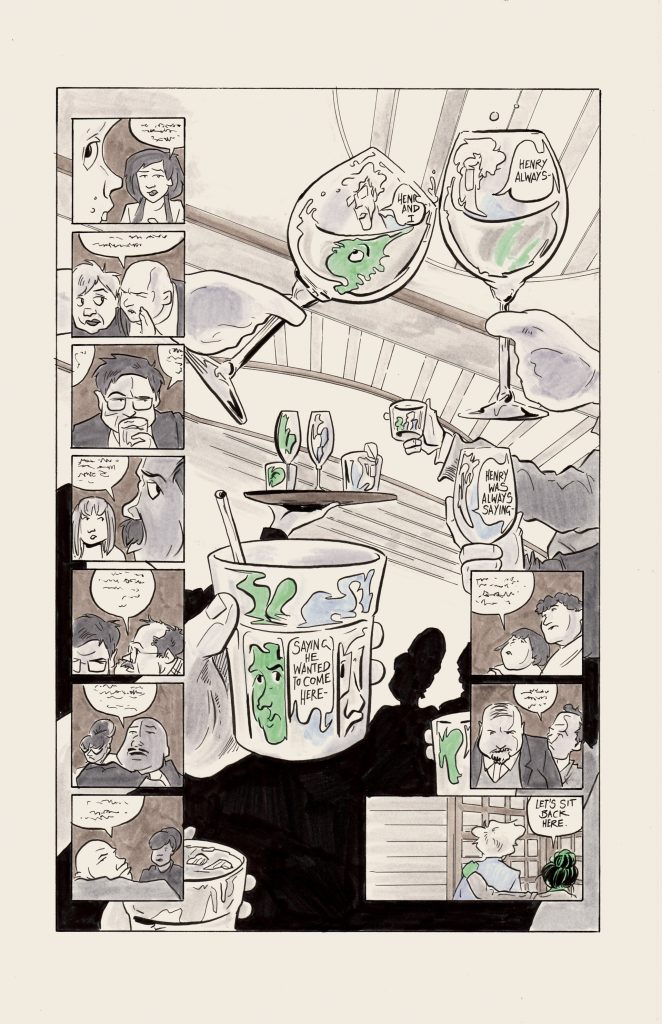

Page from The Ex-Wives of Frankenstein, written and drawn by Richard Fairgray.

Page from The Ex-Wives of Frankenstein, written and drawn by Richard Fairgray.

Constraints of each medium are also tools. Comics writers must make their medium’s constraints work for them, just like a screenwriter or novelist. Unlike prose, budget and page count constraints play a significant role in comics and screenwriting. If the budget is small, a comics writer will have to develop more story with less art, and a screenwriter will have to replace higher budget scenes with more contained ones. The prose writer typically doesn’t have to make more with less.

Conjuring images and manipulating space and time is at the core of writing, and the techniques a writer utilizes for a medium are determined by that medium’s relationship to images, space, and time. Keeping those relationships in mind when switching from writing one medium to another will set a writer up for a successful transition.

Jessica Maison is a sci-fi, fantasy, and horror author, screenwriter, and comic creator. Plastic Girl is her coming-of-age ecopunk YA novel series set in a climate apocalypse. She is the writer of the award-winning graphic novel series Mary Shelley’s School for Monsters, and her short comics have been featured in anthologies such as Cthulhu is Hard to Spell and Nightmare Theater. She is an IBPA Benjamin Franklin Gold Award winner and Foreword INDIES Award nominee. Her sci-fi speculative short stories have been published by Terraform, and she is the founder of Wicked Tree Press.