Taking Humor Writing Seriously

by Ira Nayman

A few years ago, I was on a panel on Humorous SF at a convention (an occupational hazard, given what I write). I opened with well-rehearsed remarks about how there seemed to be a resistance to my beloved subgenre among major publishers. Before I could get very far, a person in the audience stood up and said, “Isn’t it true that there aren’t a lot of humorous sci-fi stories because they’re hard to write?”

A few years ago, I was on a panel on Humorous SF at a convention (an occupational hazard, given what I write). I opened with well-rehearsed remarks about how there seemed to be a resistance to my beloved subgenre among major publishers. Before I could get very far, a person in the audience stood up and said, “Isn’t it true that there aren’t a lot of humorous sci-fi stories because they’re hard to write?”

Hmm…

I can’t argue with that. I view writing humor as drama+: A comic story must do everything a dramatic story does (it has to have characters the reader cares about and an engaging story), plus it has to make the reader laugh. Humorous genre writing can be considered drama++: It has to do everything a dramatic story does, plus make the reader laugh, plus contain genre tropes (aliens or robots for science fiction, magic systems for fantasy, dread for horror, and so on). I write satire, which adds another layer onto this formula—by now, I’m sure you can do the creative math.

The Craft

An important thing to note about this is that all of the elements have to work in order for the story to work. If the humor is weak, the reader won’t enjoy the story even if they like the characters. If the writer hasn’t done anything new with genre tropes, the reader won’t enjoy the story even if they are laughing. And of course, if the characters or plot are weak, the reader won’t—you know. Those are a lot of balls to juggle, so it should be no surprise that it’s hard to pull the act off.

(For purposes of this essay, I’m talking about works that are primarily humorous. Humor is often used as relief in adventure or dramatic stories, but in short bursts; I’m talking about writing a work where the humor flows throughout.)

The good news is that the craft of humor can be learned as much as the more general craft of writing. There are many books and online resources that do just that. These resources should make you aware of such things as: the form of jokes (setup—punchline—topper); how to let humor bubble up from character, plot, and their interaction; the variety of comic devices (exaggeration, understatement, juxtaposition of the absurd, puns and other wordplay, and more); the importance of the improv idea of yes/and; and various other considerations I do not have the room to go into here.

What makes for a good comic character? Often, all you need to do is to take one aspect of human psychology and push it to absurd limits. French playwright Molière was famous for this, as one can tell just by looking at the titles of his works: The Miser, The Misanthrope, The Imaginary Invalid.

Analyzing Humor

At the same time, it is important to read and watch broadly in the genre with an analytical eye. What makes you laugh? What tries to make you laugh and fails? How do they both work, and why does one succeed where the other doesn’t? As you grow as a comic writer, you’ll start to combine in new ways what you loved in previous works, shaping those devices into something uniquely your own.

Some writers are uncomfortable with this analytical approach. They should embrace it. I once took a course in the Social and Political Aspects of Humor. One of the first things the professor said on the first day of lectures was: “You may be under the impression that analyzing humor will kill it. Most of the students who have taken the course have found that to be untrue.” I couldn’t agree more. If anything, I found my appreciation for well-written humor increased the more I analyzed it.

This analytical approach is especially helpful when it comes to comic dialogue. Record a conversation, then compare how real people speak to how characters in comedies speak. (Spoiler: They’re very different.) In fact, great comic dialogue is like music: Not only does it have a rhythm that can be timed with a metronome, but it usually contains motifs that it repeatedly comes back to. Listen to “Who’s on First?” by Abbott and Costello, “The Argument Clinic” by Monty Python, and “Why a Duck?” by the Marx Brothers. Note, as well, how pauses can be employed as both a comic element in themselves and to allow the audience room to laugh.

Craft can and must be learned. What you do with that craft, the stories you choose to tell, and the way you choose to tell them is the art you have to provide yourself.

The Art of Writing Humor

The world is an artist’s raw material, so with humor, as with any other genre, you need to constantly pay attention to what is around you. Look for the odd, unusual things that stick out of their environment. (For example, years ago I started to take pictures of random pieces of clothing I found on streets. Try to imagine what that could be about.) In a similar vein, people often speak or act in strange ways, frequently involving discrepancies between what they say and how they act (what is generally labeled “hypocrisy”). That, if approached correctly, can yield very funny results.

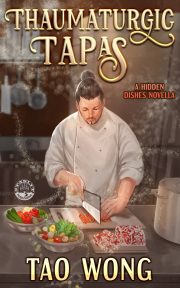

The obvious examples of humorous speculative fiction are Douglas Adams and Terry Pratchett (and, more recently, John Scalzi and Martha Wells), and I would encourage those interested in the subgenre to start there. There are a lot of other books worth considering, though, including classics like John Sladek’s Roderick novels or Keith Laumer’s Retief novels and short stories. But real gems can be found in the works of living writers published by smaller presses or self-published, where authors like Mitis Green (whose novel, The Ardley Effect, is the closest thing you’ll get to a Douglas Adams novel not written by Douglas Adams) and Cait Gordon (Iris and the Crew Tear Through Space—a fun romp with a strong positive message about disability rights) can be found. Not gonna lie: There’s a lot of bad writing out there too—because writing humorous speculative fiction is hard. But it’s worth picking the dross to find the gems.

Why, given its complex difficulties, write humor? Life is hard. We all experience disappointment, pain, and loss. Books can generally help us cope by giving us an opportunity to escape for a few hours. While humor can certainly do this, it also has a unique advantage. When we laugh, endorphins are released into our brains; they are the brain’s painkillers. Endorphins are, in short, a natural high. This comes on top of the escapism that a well-told story affords.

Some things that are hard are not inherently worth doing (e.g.: licking your nose). But many hard things, when successful, are of benefit to the world. Authors and mainstream publishers take note: The world could always use more humor.

Ira Nayman is the author of eight novels and 40 short stories that have been published. He was the editor of Amazing Stories magazine; The Dance, his first anthology as editor, was published in 2024. He is currently an editor with Donovan Street Press.