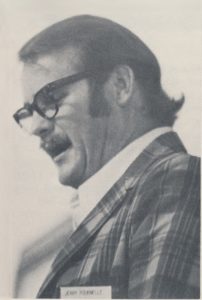

Jerry Pournelle: SFWA Historian

by Michael Capobianco

I first encountered Jerry Pournelle in the early 80s on the pages of the computer professional magazine Byte, where he had a column called “Chaos Manor.” I had just purchased an expensive Texas Instruments 99/4 home computer and was writing some primitive game software for it with friends from college. Jerry’s column was generally the most readable part of the magazine, and it was written at my beginner level. Strangely, it seemed to always consist of Pournelle writing about some new piece of software or hardware that he couldn’t get to work. That was pretty common in those days when computers were new and compatibility was often a problem. Most importantly, though, he was a science fiction writer and was writing on a computer, something I aspired to do but which seemed beyond reach.

Jump forward ten years to when I had figured out how to write on a computer and (significantly) how to print a manuscript for submission so it didn’t look like it was written on a computer. When that resulted in publication of a book co-written with William Barton, I joined SFWA, not knowing anything about it, and signed up for GEnie, a pre-internet phone modem bulletin board service run by General Electric that offered access to published science fiction and fantasy writers. It was jam-packed with SFF writers of every stripe. Almost immediately, I ran into Jerry in the private SFWA “roundtable.”

GEnie

I might jokingly say that on GEnie Jerry performed some of the same things he did in his computer columns, and there’s some truth to that. He had served as SFWA President from 1973 to 1974, chaired SFWA’s Grievance Committee (Griefcom) from 1974 to 1978, managed a reportedly very successful Nebula Awards Weekend in Los Angeles, and edited a Nebula Awards anthology. Jerry had founded SFWA’s Emergency Fund with Robert Silverberg, and they still managed it. He was oft-published both solo and in collaboration with Larry Niven and had been nominated for a Nebula twice. All of this gave him a vast experience of the organization in all its incarnations, more than anyone else on GEnie except Damon Knight, who primarily served as a provocateur. Jerry shared many anecdotes of SFWA’s past successes and controversies in a way that gave us new members a real glimpse of the organization’s history, filtered, as it was, through Jerry’s worldview. His perspective was firmly rooted in the idea that SFWA should be, first and foremost, concerned with the business of professional writing and was too often distracted by what he called “throwing parties and giving awards.” He strongly believed that SFWA’s admission criteria were too lax and was a participant in the ongoing “requal wars” that resurfaced in earnest in the organization every few years, focused on changing back to the earlier rule that Active (Full) membership required requalification based on continuing professional publication.

I might jokingly say that on GEnie Jerry performed some of the same things he did in his computer columns, and there’s some truth to that. He had served as SFWA President from 1973 to 1974, chaired SFWA’s Grievance Committee (Griefcom) from 1974 to 1978, managed a reportedly very successful Nebula Awards Weekend in Los Angeles, and edited a Nebula Awards anthology. Jerry had founded SFWA’s Emergency Fund with Robert Silverberg, and they still managed it. He was oft-published both solo and in collaboration with Larry Niven and had been nominated for a Nebula twice. All of this gave him a vast experience of the organization in all its incarnations, more than anyone else on GEnie except Damon Knight, who primarily served as a provocateur. Jerry shared many anecdotes of SFWA’s past successes and controversies in a way that gave us new members a real glimpse of the organization’s history, filtered, as it was, through Jerry’s worldview. His perspective was firmly rooted in the idea that SFWA should be, first and foremost, concerned with the business of professional writing and was too often distracted by what he called “throwing parties and giving awards.” He strongly believed that SFWA’s admission criteria were too lax and was a participant in the ongoing “requal wars” that resurfaced in earnest in the organization every few years, focused on changing back to the earlier rule that Active (Full) membership required requalification based on continuing professional publication.

First Lessons

Many of Jerry’s anecdotes on GEnie showed that SFWA had accomplished much, and some showed its sillier and/or more combative side. What did we learn? We learned that Somtow Sucharitkul’s cat had peed in his box of important SFWA documents when he was SFWA Secretary in the mid-80s (the loss of which still bedevils the organization today). We learned that SFWA had conducted a mass audit of Ace Books that turned up a lot of money owed to SFWA members. We learned that SFWA had intervened to help get J. R. R. Tolkien’s US rights to The Lord of the Rings back (see Part 1 and Part 2 of “A Brief History of SFWA: The Beginning”). We learned there had been a long and vicious fight over creating an official SFWA tie (don’t ask) and a Fellowship membership category.

Some SFWA wounds were still open after many years and were a touchstone for the organization in some quarters. On GEnie, one controversy that was often referenced but never fully explained was the Lem Affair. SFWA had awarded Polish SF writer Stanislaw Lem an honorary membership and then, after Lem attacked American science fiction and amid a long internal fight, had retracted it. Whether the retraction was political or simply happened because giving it to Lem was in violation of the bylaws (or, most likely, a combination of both) is still debated.

SFWA’s Victories

Some SFWA victories were still being celebrated. SFWA had successfully staged a boycott against Ultimate Publishing, publisher of Amazing Stories, when it started reprinting stories in its magazines without paying the authors. The publisher agreed to a flat rate at first and then a per-word rate, making it the first and most successful SFWA action of the sort (which would likely be a violation of US antitrust laws today). SFWA also took a stand against literary agent Scott Meredith acquiring editorial control of the well-regarded Timescape book publisher, claiming that there would be an obvious conflict of interest between the roles of agent and publisher. SFWA pursued several strategies to publicize the deal, and ultimately it was cancelled.

Jerry and Future History

Among other remarkable traits was Jerry’s consistency. He was able to repeat his stories and observations pretty close to verbatim year after year after year, first on GEnie, then on sff.net, and finally on the online SFWA Forum. That’s more than 25 years. His last post on the Forum (still visible to members) was made on September 7, 2017. He died a day later in his sleep of heart failure.

Robert Silverberg remembers him:

“Jerry Pournelle was a powerful figure in SFWA’s early years. His election as president drew some adverse comment, because he was the first president who had not had a major writing career—he had just begun selling SF and was a successor to such established pros as Poul Anderson, Gordon Dickson, and James Gunn. But very quickly he showed his mettle. In a conversation with me he listed, from memory, five areas where SFWA needed fixing, and he proceeded to fix them all.

“There was a problem with distribution of royalties from the various SFWA anthologies—the trustee in charge of sending out the money was being oddly obstreperous about paying it—and Jerry solved that in what we came to see was the Pournelle manner, by simply dissolving the trusteeship arrangement, thus leaving the recalcitrant trustee high and dry, and turning the distribution of royalties over to SFWA’s agent, Richard Curtis. Thinking that it was unfortunate that the best work of Robert A. Heinlein and other Golden Age writers had been done before the inception of the Nebulas in 1966, he invented the Grand Master award and gave the first one to Heinlein. (Others, like Williamson, Simak, and De Camp, received their awards in short order.) In many other ways, Jerry operated in a brisk, no-nonsense manner, seeing to it that SFWA was financially stable and rationally administered.

“After I devised the Emergency Medical Fund, I chose Jerry as my co-administrator, he and I being close friends who saw eye to eye on many things, and for years thereafter the two of us ran the fund in complete harmony. He also gave me a good lesson in Christian compassion—Jerry was a religious man—when someone who was only marginal as a writer and had done Jerry actual harm in an area outside the SF world asked for an EMF grant, not for himself but for his wife, who was not even a writer. I voted against the grant, but Jerry, turning the other cheek, said that we should overlook the various negative factors of the application and approve it anyway, simply as a good deed. I could not object to that.

“Jerry was hard of hearing and spoke in a very loud voice, which led some people to think that he was an unruly ruffian. He wasn’t. He was a splendid human being and I was happy to have enjoyed his friendship for so many years.”

I only met Jerry in person once, at a SFWA Business Meeting, and we were never friends. I often felt we were adversaries, but I realized at some point that a great deal of my understanding of what SFWA was and what it could be were formed in part by his SFWA anecdotes and arguments on the online boards. I’ve recently been appointed SFWA Historian, a daunting task without any particular duties. Still, I have a collection of SFWA publications and papers. I am working with SFWA’s History Committee to archive and preserve what I’ve collected at Northern Illinois University to make it safe from cat pee forever.

Michael Capobianco is co-author with William Barton of the SF books Iris, Alpha Centauri, Fellow Traveler, and White Light. He has published two solo science fiction novels, Burster and Purlieu, as well as short fiction. Capobianco was President of SFWA from 1996 to 1998 and again in 2007–2008. He currently serves as SFWA Historian in addition to chairing and co-chairing several SFWA committees.

Michael Capobianco is co-author with William Barton of the SF books Iris, Alpha Centauri, Fellow Traveler, and White Light. He has published two solo science fiction novels, Burster and Purlieu, as well as short fiction. Capobianco was President of SFWA from 1996 to 1998 and again in 2007–2008. He currently serves as SFWA Historian in addition to chairing and co-chairing several SFWA committees.