Legacy of the Iron Curtain: Writing Ukrainian Fiction in a Post-Soviet World

by A.D. Sui

Editor’s note: This piece is part of a rolling series, Writing from History, in which creators share professional insights related to the work of using historical elements in fictional prose.

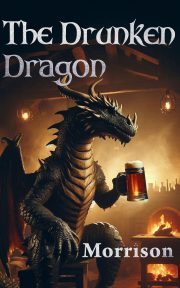

In early 2024, I was going through the editorial process for my short story “Svitla,” featured in Embroidered Worlds: Fantastic Fiction from Ukraine and the Diaspora, when my editor lovingly pointed out that the original title “Svet” should be replaced by the Ukrainian “Svit.” Several terms throughout the story were russified translations that I simply embraced as fact, having been raised in the mixed-language city of Kharkiv right after the fall of the Soviet Union.

Photo of A.D. Sui, age 4, Kharkiv, Ukraine.

When most Westerners think of Russia, several things come to mind: ballet, hockey, classic literature, bears, doping allegations. Russia is hard to miss, both geographically and culturally. When Westerners think of Ukraine, they usually think of Chernobyl. If one wishes to write a quintessential story about Ukraine, one must write about Chernobyl.

As a diaspora Ukrainian author, writing for a predominantly Western audience, my task is twofold. First, I must convince the reader that my story is qualitatively different from a Russian story. This is already a challenging task since few are aware of Ukrainian folklore, geography, and political landscape. Even in this post, I write about Ukraine in relation to Russia, to give it some grounding. Due to geographical proximity, much of Slavic folklore is quite similar, thematically. Whoever shouts louder claims the story and disseminates it through the literary world. Ukrainians can never shout loud enough, it seems.

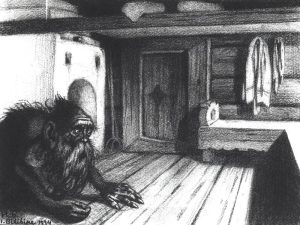

What gives Ukrainian stories their unique tone is their symbiotic relationship to the natural environment. Most of these stories were crafted when Ukrainian society revolved around farming and hunting, and both respect for wilderness and co-existence permeate every tale. Take the domovyk, for example, a spirit that inhabits a home, usually in the form of a tiny, hairy man. Don’t worry, he’s quite adorable. The domovyk protects the home from evil spirits, but in return, the home-dwellers must keep the house clean and vibrant. Otherwise, the domovyk can throw fits and break dishes and glasses. Keep the house tidy and welcoming, and evil spirits will be kept at bay. Reduce conflict. Bake bread. Co-exist.

Illustration by Ivan Bilibin (1876-1942) – File:Domovoi Bilibin.jpg, Public Domain.

The second task in writing a Ukrainian story is to convince my reader that, as a qualitatively different narrative, the story is one worth telling. Ukraine has little taste for conquest or expansion, and this is reflected in our stories. We picked a spot 1,500 years ago and said, “This is a good spot.” and stayed there since. Which isn’t to say that most of our stories are “cozy,” but rather they’re smaller in scale, focusing largely on the agency of an “underdog” character. These are not necessarily feel-good stories with happy and victorious endings. How can they be, when most of Ukrainian history is marked by resistance against Russian culture and oppression? They’re stories about beauty and joy made in the cracks, always made, because it is in the Ukrainian ethos to make and create rather than take or receive passively.

My biggest challenge as a Ukrainian writer has been to balance the authenticity of what Ukrainian stories should be with their marketability. Often, I question the very nature of my Ukrainian identity since I can’t recall it without using the Russian language. When I remember my childhood in Ukraine, it comes to me in Russian. When I remember folk stories and cartoons, they also come in Russian. It’s only now, as writer and adult, that I understand how my entire Ukrainian identity had been shaped through the Russian lens, its language, and its culture. How can I then be trusted to write Ukrainian fiction, when the very act of thinking about it is a linguistic betrayal, when the word for light is svet and not svit?

Most of my works about Ukraine never use its name. In “Hunt,” first published in Apparition, a nameless protagonist joins forces with the woods to protect her village from faceless and equally nameless invaders. “Svitla” is the first story that refers to Ukrainian geographical locations, but at its core, it’s about unyielding nature and unyielding daughters. My story “Mavka,” forthcoming in Pseudopod, is a story about an unnamed village, and a terrible hunger, but those who are aware of Ukrainian history know what it’s really about. It might be the first and the only story I will write that deals with actual, Ukrainian history.

Most of my works about Ukraine never use its name. In “Hunt,” first published in Apparition, a nameless protagonist joins forces with the woods to protect her village from faceless and equally nameless invaders. “Svitla” is the first story that refers to Ukrainian geographical locations, but at its core, it’s about unyielding nature and unyielding daughters. My story “Mavka,” forthcoming in Pseudopod, is a story about an unnamed village, and a terrible hunger, but those who are aware of Ukrainian history know what it’s really about. It might be the first and the only story I will write that deals with actual, Ukrainian history.

Works by Yelena Crane and R.B. Lemberg, both authors born in Ukraine but now writing in the United States, often follow a similar pattern: stories set in fantastical settings, in unnamed geographical locations, that are undoubtedly Ukrainian in ethos and subject matter. Conversely, Nika Murphy’s “The Ghost Tenders of Chornobyl” takes the quintessential Ukrainian setting and forces it into a conversation with current events, the war, and the uncertain future.

Similarly, so much of the Ukrainian fiction I write attempts to stand in opposition to Russia’s imperialism. These stories are about resistance, loss, and grief. They are not comfortable stories with clear resolutions because I’ve yet to see what that resolution is. The war continues, and even after it’s over, Ukraine cannot physically move itself farther from Russia’s borders. The juxtaposition will continue. My fear is that the next quintessential Ukrainian story will be about drones and civilian deaths. Instead, I want to draw attention to the people, to the small acts of love and resistance.

Maybe part of being Ukrainian is the complicated relationship with our own culture that many of us had to consciously unpack in adulthood. Maybe that’s where the meandering stories come from. No certain end. No resolution. No triumph. Not yet.

The process of de-russifying our identities has no clear end. Sometimes it’s grand and sweeping, like solidifying the Ukrainian language as the official language of all government administration. Sometimes it’s as small as learning to write “svit” instead of “svet” when we write about home.

A.D. Sui is a Ukrainian-born, queer, disabled science fiction writer, and the author of The Dragonfly Gambit and the forthcoming Erewhon novel The Iron Garden Sutra (2026). She is a failed academic, retired fencer, and coffee enthusiast. Her short fiction has appeared in Augur, Fusion Fragment, HavenSpec, and other venues. When not wrangling her two dogs, you can find her on every social media platform as @thesuiway.

A.D. Sui is a Ukrainian-born, queer, disabled science fiction writer, and the author of The Dragonfly Gambit and the forthcoming Erewhon novel The Iron Garden Sutra (2026). She is a failed academic, retired fencer, and coffee enthusiast. Her short fiction has appeared in Augur, Fusion Fragment, HavenSpec, and other venues. When not wrangling her two dogs, you can find her on every social media platform as @thesuiway.