by Emily Jiang

AN INTRODUCTION OF SORTS: To Boldly Go Where I Have Never Gone Before

“We often fear what we do not understand. Our best defense is knowledge.” –Tuvok

Over 15 years ago, when I enrolled in an MFA program for Creative Writing, I had no idea what social justice was. Around that time, I also attended the Clarion Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers’ Workshop, and I vented to my instructor Nalo Hopkinson that I felt so clueless, not knowing the meaning of POC (Person of Color), a relatively new term back then. I was not sure if I, as an Asian American, qualified to be a Person of Color. Over 15 years ago, I could not accurately spell LGBTQ, much less explain what each letter signified, and I barely understood disability issues. But a lot can change in fifteen years if one is willing to listen with an open mind and heart. I listened to many amazing, bleeding-edge thinkers from a variety of backgrounds and experiences. I listened and asked questions and learned.

This essay covers my perspective as a BIPOC writer observing the ever-changing state of publishing science fiction, fantasy, and horror (SFFH) in the United States, comparing 2009 to 2024, from how BIPOC representation has grown in the editorial staff of major magazines and publishers, to addressing the range of BIPOC-centric anthologies, to analyzing the percentages of BIPOC writers recognized on the shortlists of major SFF awards. Finally, I will speculate on the future of SFFH readership.

DIVERSITY IN PUBLISHING

“You can’t just walk away from your responsibilities because you made a mistake.” –Kathryn Janeway

Over the past fifteen years in the United States, publishing has experienced controversies and campaigns surrounding diversity. In 2009, the SFFH community experienced #Racefail. In 2014, the #WeNeedDiverseBooks movement originating on Twitter (now X) actually resulted in a change in Book Expo America’s programming when they added last-minute diverse book creators as speakers that same year. Since then, publishing has seen a much-needed acceleration in the writing, editing, and publishing of BIPOC stories to reflect the diversity of readership.

MAGAZINE STAFF

“In our century, we’ve learned not to fear words” –Uhura

The culture of SFFH is such that if you want to publish a zine, you just do it. Therefore, we are lucky to have a wide range of magazines for our readership. It would be impossible to address all the SFFH magazines out there, so this article will focus on major SFFH magazines paying professional rates, which SFWA last set in 2019 as 8 ¢ per word.

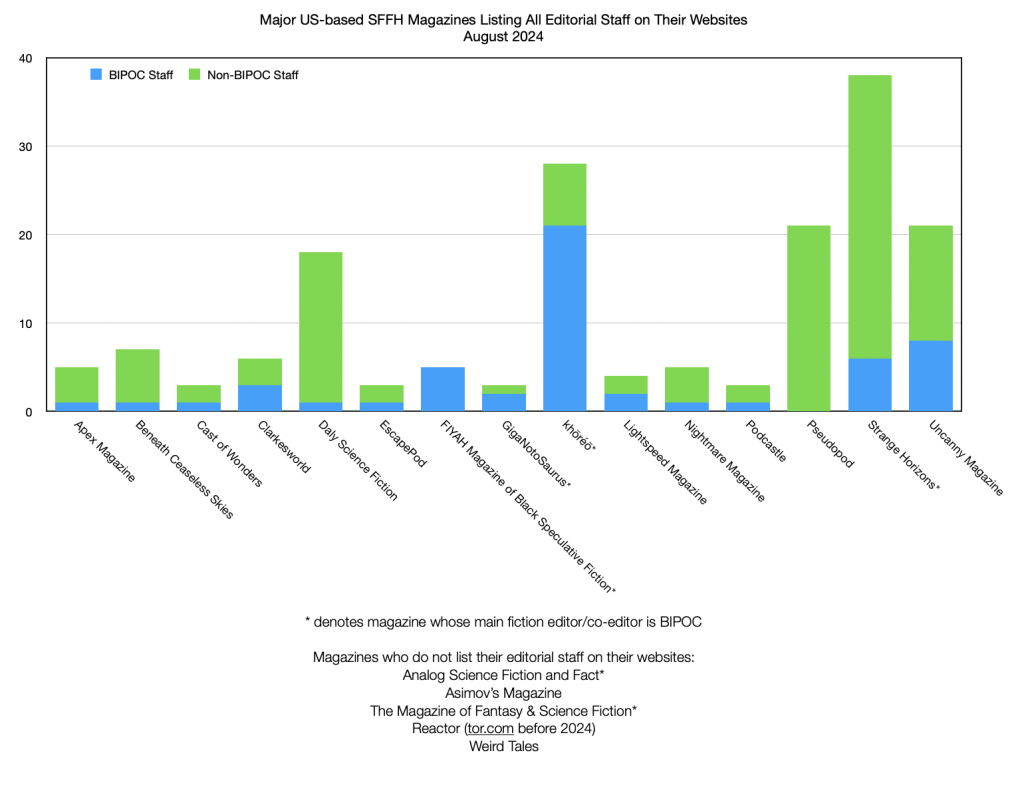

Headed primarily by white men before 2009 (with the exception of Sheila Williams, editor of Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine since 2004), the majority of the major SFFH magazines now include BIPOC among their editorial staff. Most notably, in 2020, Sheree Renee Thomas took over the editorial helm of the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, one of the oldest and most prestigious periodicals publishing SFFH. In 2022, LaShawn M. Wanak became editor of the GigaNotoSaurus. The most recent iteration of the now defunct Fantasy Magazine was co-edited by Arley Sorg from 2020 to 2023, and often promoted special submission windows for BIPOC writers. Sorg also is the Assistant Editor at Fantasy’s sibling magazines, Lightspeed and Nightmare. Strange Horizons’ fiction editorial team includes Aigner Loren Wilson and Dante Luiz. After editing for Strange Horizons, Uncanny Magazine, and Fireside Magazine, Julia Rios founded their own magazine, Worlds of Possibility. Shingai Njeri Kagunda became co-editor of Podcastle in 2021; Valerie Valdez is currently co-editor of EscapePod.

Over 10 years ago, most of these markets did not have any BIPOC on their editorial staff, so I’m pleasantly surprised to see the majority of magazine staff include at least one BIPOC (though often only one). Most of those positions are assistant editors or first readers. Out of the magazines who do have BIPOC on editorial staff, six are actively led by BIPOC in fiction, and FIYAH is BIPOC-centric and run by a completely BIPOC team.

ANTHOLOGIES

“The idea of fitting in just repels me.” –Guinan

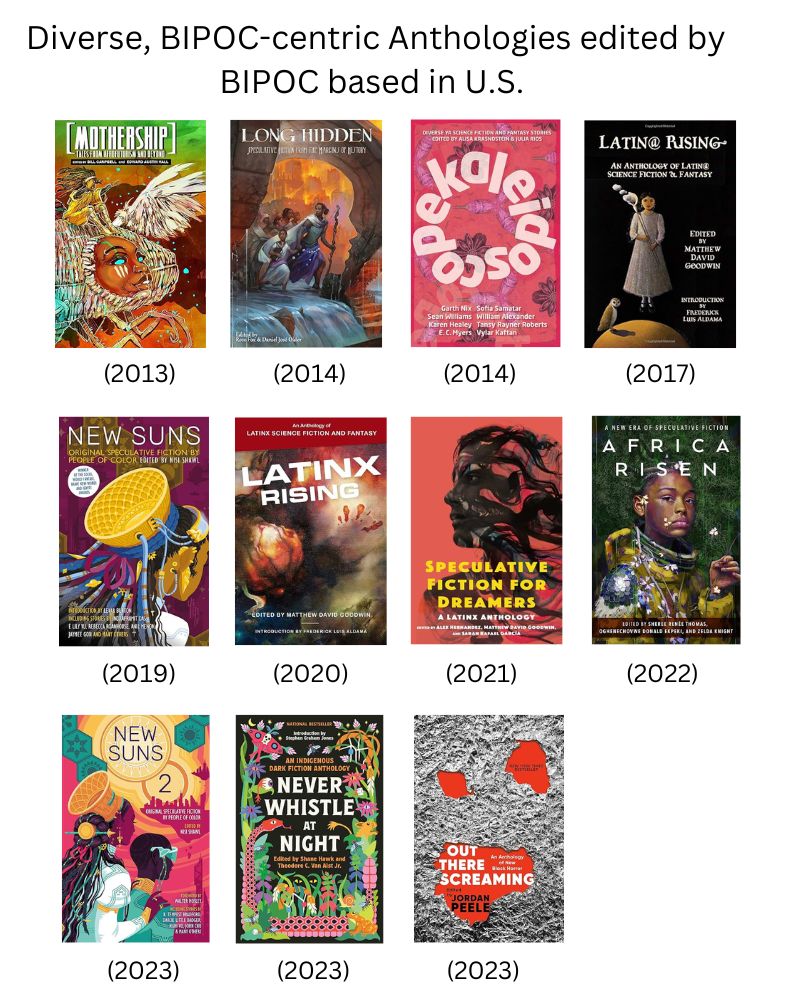

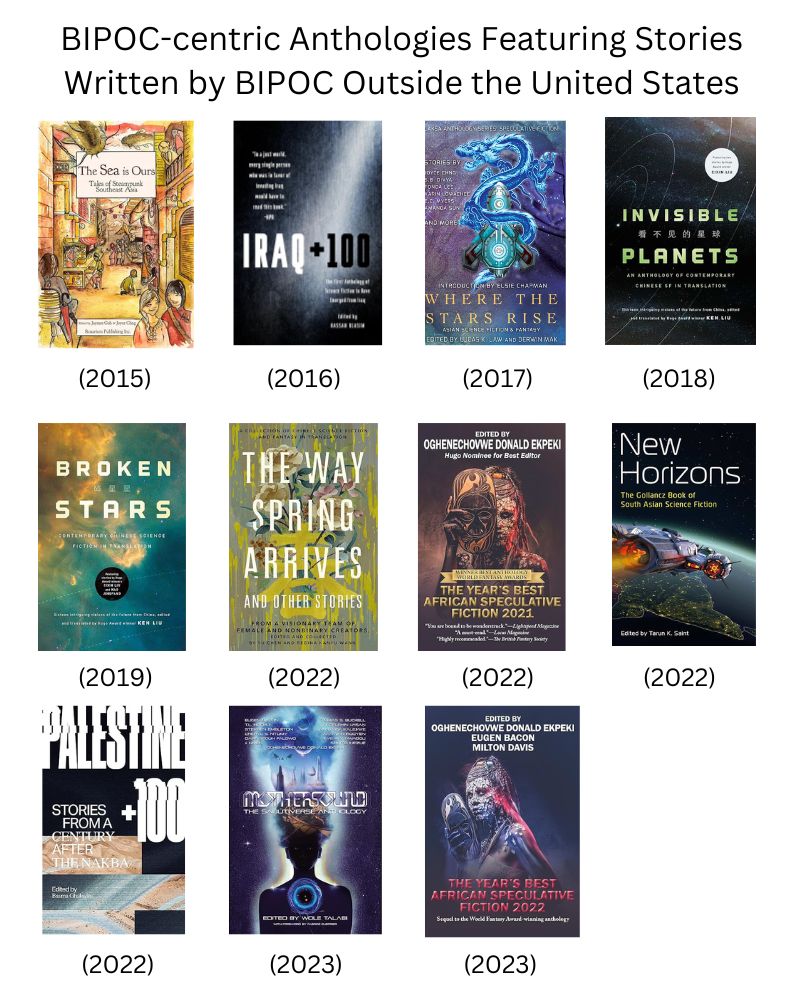

Since 2009, many amazing SFFH BIPOC-centric anthologies have been edited by BIPOC:

While there are plenty of talented Asian Americans writing SFFH, there’s not an Asian American anthology…yet.

“Don’t call me tiny.” –Sulu

While most SFFH Year’s Best anthologies have been edited by white men (with the recent exception of The Year’s Best African Speculative Fiction), a couple of series include volumes which have been co-edited by BIPOC writers. For example, John Joseph Adams’ The Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy anthologies often feature a guest co-editor who is BIPOC: R.F. Kuang for 2023; Rebecca Roanhorse for 2022; Carmen Maria Machado for 2019; N.K. Jemisin for 2018; Charles Yu for 2017. For four years, Julia Rios co-edited each annual volume of the Year’s Best YA Speculative Fiction.

BOOK EDITORS

“Who gave them the right to decide whether or not I should be here? Whether or not I might have something to contribute?” –Geordi La Forge

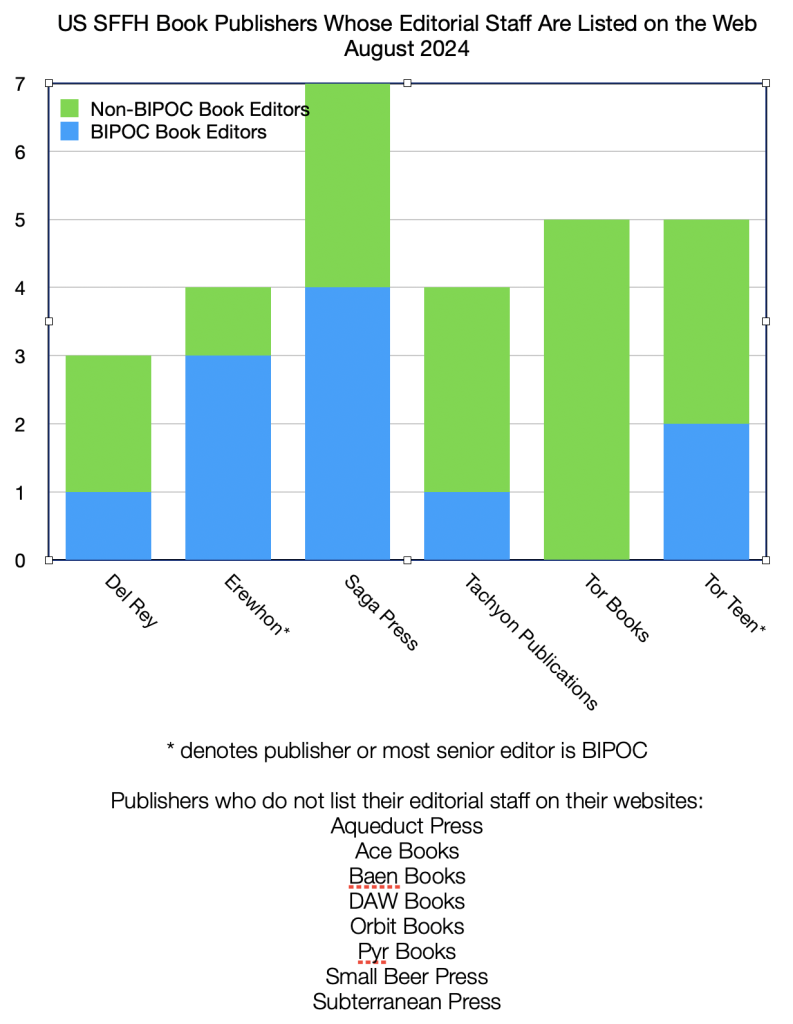

When I visited the Tor offices over ten years ago, I was delighted to meet Susan Chang, the first and only BIPOC book editor I knew in SFFH for years. Now many more BIPOC editors work in book publishing.

I was once again pleasantly surprised to see more BIPOC listed, though again most of them are junior editors. Note these are the staff of the US imprints/publishers who only publish SFFH. Unacknowledged are the many other editors at other publishing houses who are open to (but not exclusive to) publishing SFFH, which is truly a part of the mainstream now.

MAJOR AWARDS FINALISTS

“I wouldn’t be very much of a friend if I let you give up on a lifelong dream, now would I?” –Geordi La Forge

Several SFFH awards have rebranded within the past few years. In 2016, the World Fantasy Award trophy was redesigned into a tree holding a full moon in its bare branches. Previously the award was a bust of author H. P. Lovecraft, now known for his extreme racism. In 2019, the James Tiptree, Jr. Award was renamed the Otherwise Award, and according to its website: “In the beginning, the award’s focus was on gender alone. Over the years, that focus expanded, but the award’s goal is still to make the world listen to voices that they would rather ignore.” In 2020, the Hugo Awards witnessed the renaming of the John W. Campbell Award, which it administers, to the Astounding Award for Best New Writer, in response to 2019 winner Jeannette Ng’s denouncement of the award’s name.

I will focus on two awards receiving readership votes, the Hugos and the Locus Awards, to show the changing trends of SFFH readership in Worldcon participants and Locus readers.

Scholar Farah Mendlesohn asserts that the rise of social media has made public various discourses and thereby accelerated the progressive thought processes within a few short years (Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts, 2021). After reviewing the Hugo finalists since 2009, I have observed that all literary categories now feature BIPOC writers. Note that the Hugo Awards experienced unusual nomination interference from the Sad and Rabid Puppies in 2013-2017. But every year since 2018, the Hugo shortlist for every fiction category (Best Novel, Best Novella, Best Novelette, Best Short Story) has included at least one work by at least one BIPOC writer. This is significant progress compared to the twenty Hugo finalists from 2009, whose writers were almost all white (except for Ted Chiang) and mostly male (except for Elizabeth Bear, Kij Johnson, and Mary Robinette Kowal).

Since 2009, the Hugo fictional nominees grew from 5 percent to a minimum of 16.7 percent BIPOC writers** regularly shortlisted since 2018. While this is progress, 16.7 percent is still significantly less than the 28 percent BIPOC population reported by the US Census in 2010. But in recent years, the shortlist has further grown in BIPOC representation, and the 2024 Hugo fiction nominees number eleven BIPOC authors among twenty-four, which is almost 46 percent, the highest in Hugo history.

**In 2015, the Hugo shortlist expanded from five to six nominations per category. One BIPOC writer out of six total per category is 16.7 percent.

A similar shift happened in the Locus Awards, which is determined by popular vote of its readers with double votes for each subscriber. In 2009, the Locus Awards published a finalist list that had only one BIPOC writer (Ted Chiang again) whose work was nominated among thirty-five total finalists in seven different categories.

In 2024, the Locus Award fiction shortlist expanded from five to ten finalists per category, and now features ten categories: Science Fiction Novel, Fantasy Novel, Horror Novel, Young Adult Novel, First Novel, Novella, Novelette, Short Story, Anthology, and Collection. Out of 100 fiction finalists, forty-seven works were created by BIPOC writers. That’s 47 percent BIPOC representation at the Locus Awards for their fiction. Most significantly, out of the ten finalists listed for First Novel, six novels were written by someone who was BIPOC. That’s 60 percent representation!

As a first-time attendee of the Locus Awards in 2024, I was impressed that more than half of the panelists speaking at the Locus Awards were BIPOC (full disclosure, I was a panelist). Granted, most panelists were local to the San Francisco Bay Area venue, which is one of the most ethnically diverse communities in the US, but many speakers were also Locus Award finalists. I left the Locus Awards with great hope for the growth of BIPOC creators in SFFH.

***Awards Event Interlude***

“It’s the unknown that defines our existence. We are constantly searching, not just for answers to our questions, but for new questions.” –Benjamin Sisko

In 2014, I felt honored to speak on a diversity panel at the Nebula Awards with Nalo Hopkinson, and Samuel Delany. It was the first creative panel I’d ever spoken on where everyone was BIPOC and writing in English. I was nervous because I did not want to make a fool of myself and disappoint Nalo. After that panel, she said, “I remember diversity issues used to worry you.” She gave me a solemn nod and said, “I think you’ve figured it out.” I was overwhelmed with gratitude that Nalo, who teaches so many people, remembered my fears and acknowledged my efforts to learn and grow. I continue to learn, to question, to understand, because these topics are always refining their nuances.

OUR FUTURE READERSHIP

“Vulcan parents never shield their children from the truth. Doing so would only hinder their ability to cope with inevitable difficulties.” –Tuvok

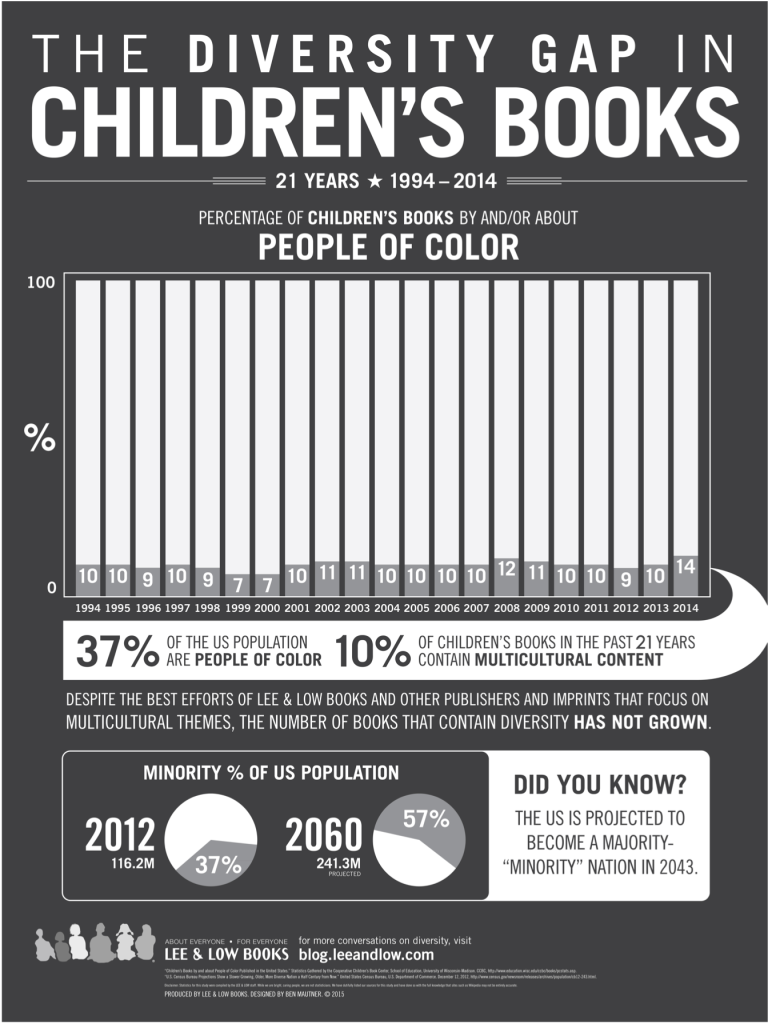

After the debut of my picture book Summoning the Phoenix in 2014, I was curious about who would be reading my book, and I wondered if Asian American children (including mixed race) would see themselves in the illustrations. A year later, my publisher, Lee & Low, released articles about the Diversity Gap in Publishing. They published a Diversity Baseline Survey of Publishing Professionals in 2015, repeated the survey in 2019, and published it again in 2023.

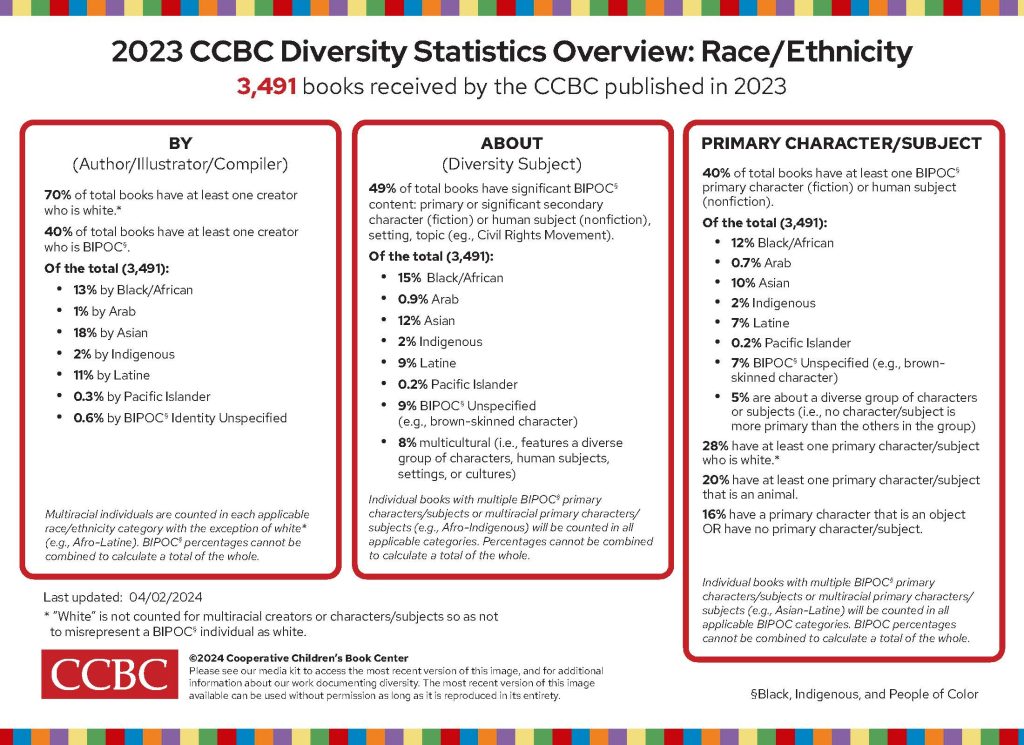

Lee & Low also used statistics collected by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center (CCBC), who annually track racial representation in all the children’s books traditionally published in the United States. For twenty years, roughly 10 percent of new children’s books have featured any major character of color, completely failing to reflect the young readership of the US.

In July 2011, the US Census reported for the very first time that the birth of non-Hispanic all-white babies in America dipped below 50 percent. So, in 2014, over half of American-born three-year-olds saw themselves in roughly 14 percent of the newly published books. Very depressing.

“Things are only impossible until they’re not.” –Jean-Luc Picard

For 2023, the CCBC reported better statistics:

Forty percent of the children’s and YA books published in 2023 in the United States feature BIPOC characters! It’s not quite the 50 percent necessary to match the young American readership, but definitely an improvement from 10 percent.

In 2018, the US Census projected that the US would become a majority-minority country by the year 2045, so no race will be the majority. The future for the United States is clear. We will be assimilated. Resistance is futile.

A CONCLUSION OF SORTS: The Final Frontiers

“There is only one thing I want from you. Find something you love, then do it the best you can.” –Benjamin Sisko

Considered a niche genre during the previous century, SFFH is now mainstream thanks to the international record-breaking successes of the Harry Potter books and the Lord of the Rings movies at the turn of the century. Over twenty-five years ago, most science fiction was written in English and published in the US and the U.K. But now there is a growing, thriving community of SFFH all around the world.

Founded in 1965, Science Fiction Writers of America (SFWA) changed its official name in 1991 to the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America (sorry horror writers, you’re likely lumped in with fantasy). In 2022, SFWA dropped “of America” and rebranded to the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Association to acknowledge the growth of its non-US members.

For SFFH written originally in English, there is wonderful fiction originating from Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, Malaysia, India, and various parts of Africa.

Some popular SFFH is being written in languages that are not English. The Three Body Problem by Cixin Liu was the bestselling SF novel in China. Its English translation achieved bestseller status in the United States and won a Hugo Award for Best Novel. There are more and more wonderful stories being translated into English every year.

In 2012, I journeyed to China, where I gave a lecture to the Science Fiction Club at Beijing Normal University. The title was “Is Science Fiction Falling or Dying in the United States?” The short answer was “No. Because science fiction should always be evolving as science itself is evolving.” Those adults who wish to only read the stories of their youth are not keeping up with science.

What was considered cutting-edge science fifty years ago is taught to schoolchildren as part of their customary curriculum, and much of it has been refined and/or debunked. Think of the smallest particle in the universe; roughly 200 years ago, the educated person would say it was the atom. From 1897 until 1964, the answer would have been the electron. Since 1964, we now consider the smallest particle to be a quark. Quarks have always been around, but people did not know they existed until less than 100 years ago.

We are always changing. We are always “discovering” and “renaming” what was already there. We continue to tell our stories that are new-to-us in our own voices, so that our future will read them, then tell stories that are new-to-them in their own voices. Our stories will never be forgotten, as long as we continue telling and retelling them.

Live long and prosper.

Emily Jiang is the author of Summoning the Phoenix, which was listed among the Best Children’s Books of the Year at Kirkus Reviews and The Huffington Post. Her prose and poetry have been published in Weird Tales, Strange Horizons, and Uncanny Magazine. Her choral compositions can be heard at Interfictions.

Emily Jiang is the author of Summoning the Phoenix, which was listed among the Best Children’s Books of the Year at Kirkus Reviews and The Huffington Post. Her prose and poetry have been published in Weird Tales, Strange Horizons, and Uncanny Magazine. Her choral compositions can be heard at Interfictions.