A Brief History of SFWA: The Beginning (Part 2)

by Michael Capobianco

Editor’s note: This piece is the second in a two-part overview of the first year of SFWA, curated by a member of the organization’s History Committee. Part 1 is available here.

Damon Knight was now president of SFWA, Editor/Writer/Publisher of the Bulletin, and chair of a one-person Contracts Committee/Griefcom. It was at about this point that SFWA was becoming unmanageable for one person. Enter Lloyd Biggle, Jr., the newly elected Secretary-Treasurer. Biggle struck Knight as someone who was “sucker enough to take that job (Secretary-Treasurer) and do it conscientiously,” which was apparently an extremely accurate assessment.

Knight recalled in Bulletin #54, “Lloyd not only served two terms as Secretary-Treasurer and did dozens of other jobs for the organization, he set up the trustee system and served on it for years, while I got out after two terms and lay in a hammock. Furthermore, it was Biggle who proposed the annual SFWA anthology as a means of making money for the organization. And from that came the idea of the annual awards and the trophies and the banquets and this whole apparatus. Of course, it had crossed my mind that we might do something like that eventually, but in the beginning, we were too poor. It was our share of the royalties that made it possible.”

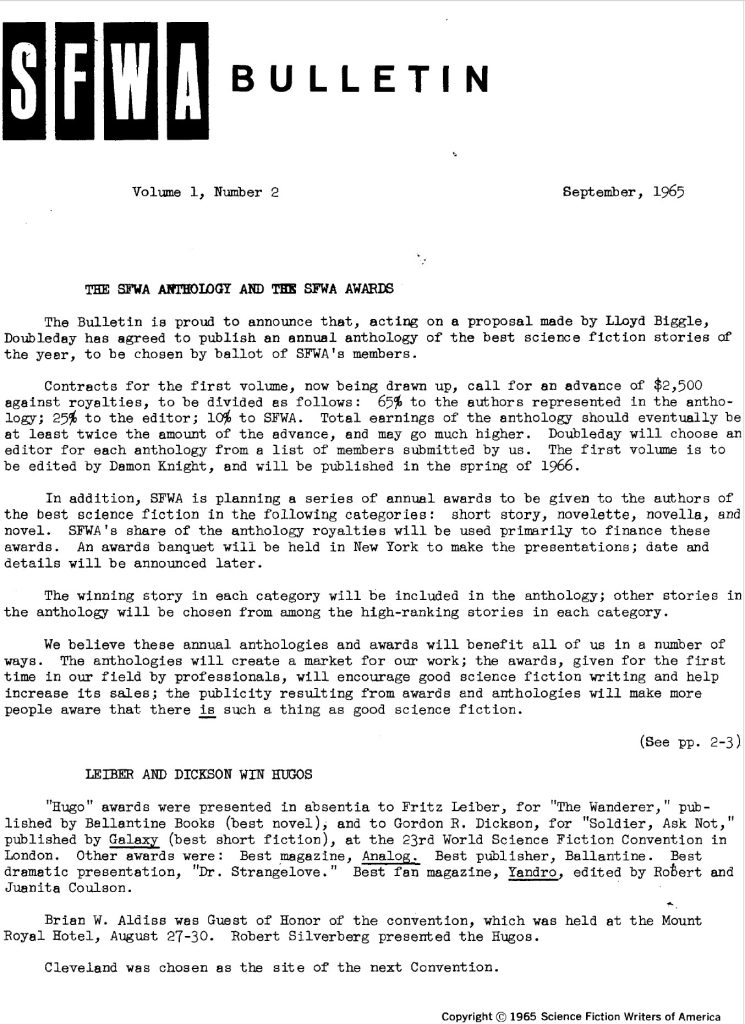

Figure 4. SFWA Bulletin, Volume 1, Number 2. Scanned copy from the collection of Michael Capobianco. September, 1965.

Things were happening fast. The second issue of the Bulletin is dated September 1965 and starts off with the announcement that Doubleday had agreed to publish an annual anthology of the best science fiction stories of the year, to be chosen by ballot of SFWA’s members (Figure 4). Ten percent of the $2,500 advance would go into SFWA’s coffers, the remainder to be split 65 percent to the contributors, 25 percent to the editor (who, for the first anthology, perhaps not coincidentally, would be Knight himself). $2,500 may not sound like much, but it’s a little less than $25,000 in 2024 dollars, and SFWA’s share was the equivalent of 1965 dues from 83 members.

The awards for best novel, novella, novelette, and short story would also be held annually. Nominations were to begin immediately; nominations for the novel award closed in January 1966; for all other categories, in mid-November 1965. It was agreed that editorship should rotate, and be chosen from the roster of SFWA members.

The rules for the new awards were put together rapidly owing to the short time to get the anthology ready. There were several differences from the Hugo Award rules of the time, which is an obvious comparison. At the time, the Hugos only had two prose fiction awards, for novel and short fiction. The SFWA categories would be defined solely by length: short stories less than 7,500 words; novelettes 7,500 to 17,499 words; novellas 17,500 to 39,999 words; and novels 40,000 words or more. This appears to be the first time length-related distinctions were introduced for awards; prior to this, they had only been referenced in magazine tables of contents. There would also be a banquet held in New York City in March 1966 at which to present the 1965 awards, but the details hadn’t been figured out yet. A name for the awards was also forthcoming.

It has often been said that the primary purpose of the Nebula Awards and anthology was to earn the organization money. The statement Knight wrote for the Bulletin, however, indicated a quite different set of goals: “The anthologies will create a market for our work; the awards, given for the first time in our field by professionals, will encourage good science fiction writing and help increase its sales; the publicity resulting from awards and anthologies will make more people aware that there is such a thing as good science fiction.” Secretary-Treasurer Biggle did follow up with an addendum that the income would allow them to “broaden the scope of SFWA operations.”

The remainder of the second issue of the Bulletin was packed with information of the kind that Knight had created the organization to provide. First, a comprehensive survey of foreign markets was compiled with the aid of E. J. Carnell, a British editor, anthologist, and literary agent for many British writers at the time. A list of literary agents who handled foreign rights, along with details of the markets, was included.

Then came the first of a series of articles Knight wrote about book contracts focusing on the grant of rights and reversion clauses (“what you give to the publisher; when and how to get it back”). Breakdowns such as this were the beginning of SFWA’s long-standing Contracts Committee, which Knight headed for the first years. Knight had access to the contracts of all the major American science fiction publishers of the time, and, for example, the reversion clauses of nine major publishers are all laid out in a handy little chart.

This issue also contains SFWA’s first published correspondence from members, some followed by brief replies from editor Knight. Letters from Isaac Asimov, Frederik Pohl, John Brunner, and Tom Purdom were mostly congratulatory. Noteworthy, however, was a longish screed from Lawrence M. Jannifer which questions SFWA’s membership qualifications and aims a shot at the newly elected vice-president: “But this notion of Harlan as V.P. does something awful to me, deep inside where it hurts.” It’s difficult to say how seriously Jannifer intended the remark, but, of course, it produced an equal and opposite reaction that would show up in the next issue.

The last pages included a list of 27 new members, including future Grand Masters Andre Norton, Lester del Rey, Anne McCaffrey, and Clifford D. Simak, as well as E.E. Smith, Frank Herbert, and Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.

Early Advocacy

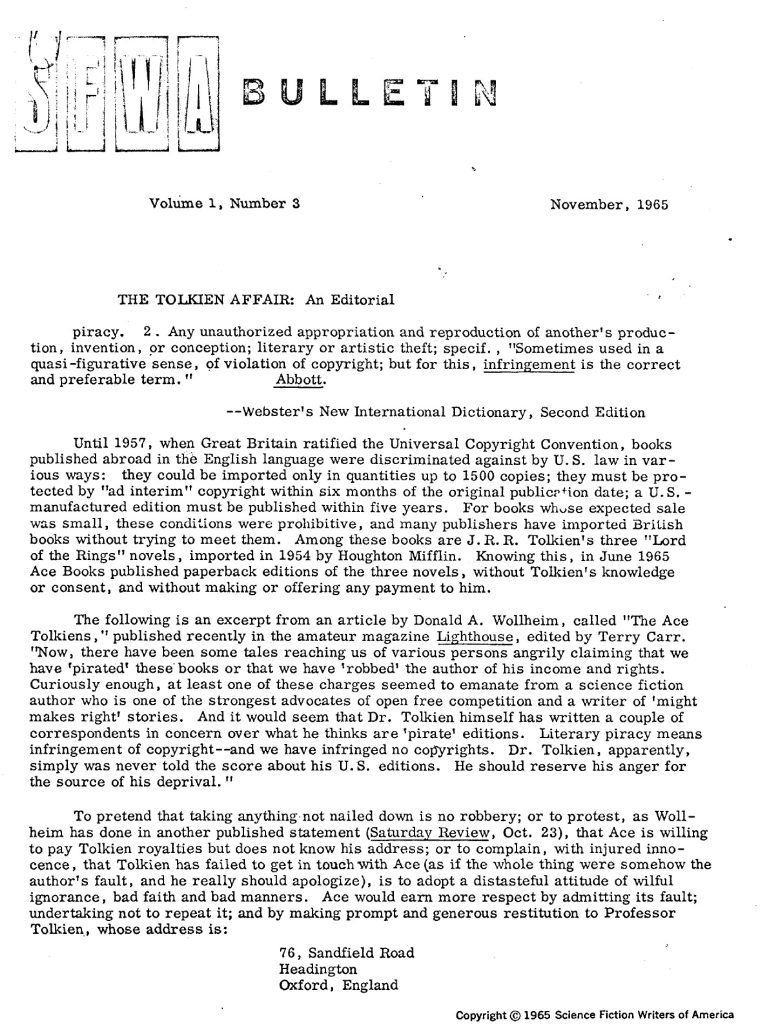

Figure 5. SFWA Bulletin, Volume 1, Number 3. Scanned copy from the collection of Michael Capobianco. November, 1965.

The Bulletin’s third issue, dated November 1965, leads off with “The Tolkien Affair: an Editorial” (Figure 5). Written by Knight, the essay indirectly accuses Ace Books editor Donald A. Wollheim, who was a charter member of SFWA, of piracy. The editorial summarizes the situation: a small number of copies of the Lord of the Rings books had been imported into the US by their publisher, Houghton Mifflin, in 1954. Due to the vagaries of US copyright law at the time, Houghton Mifflin didn’t meet specific requirements, including publishing them in the US within five years, and the books fell into the public domain in the US. Wollheim discovered this and published all three Lord of the Rings books in May 1965. The editorial summarized the situation and included an excerpt from Terry Carr’s amateur magazine Lighthouse, in which Wollheim indignantly defends his decision to publish the books.

The editorial ends with: “To pretend that taking anything not nailed down is no robbery; or to protest, as Wollheim has done in another published statement (Saturday Review, Oct. 23), that Ace is willing to pay Tolkien royalties but does not know his address; or to complain, with injured innocence, that Tolkien has failed to get in touch with Ace (as if the whole thing were somehow the author’s fault, and he really should apologize), is to adopt a distasteful attitude of wilful ignorance, bad faith and bad manners. Ace would earn more respect by admitting its fault, undertaking not to repeat it, and by making prompt and generous restitution to Professor Tolkien,” and then gives Tolkien’s Oxford address.

It was, in effect, publicly shaming Wollheim in front of a not-inconsiderable audience of science fiction writers and editors.

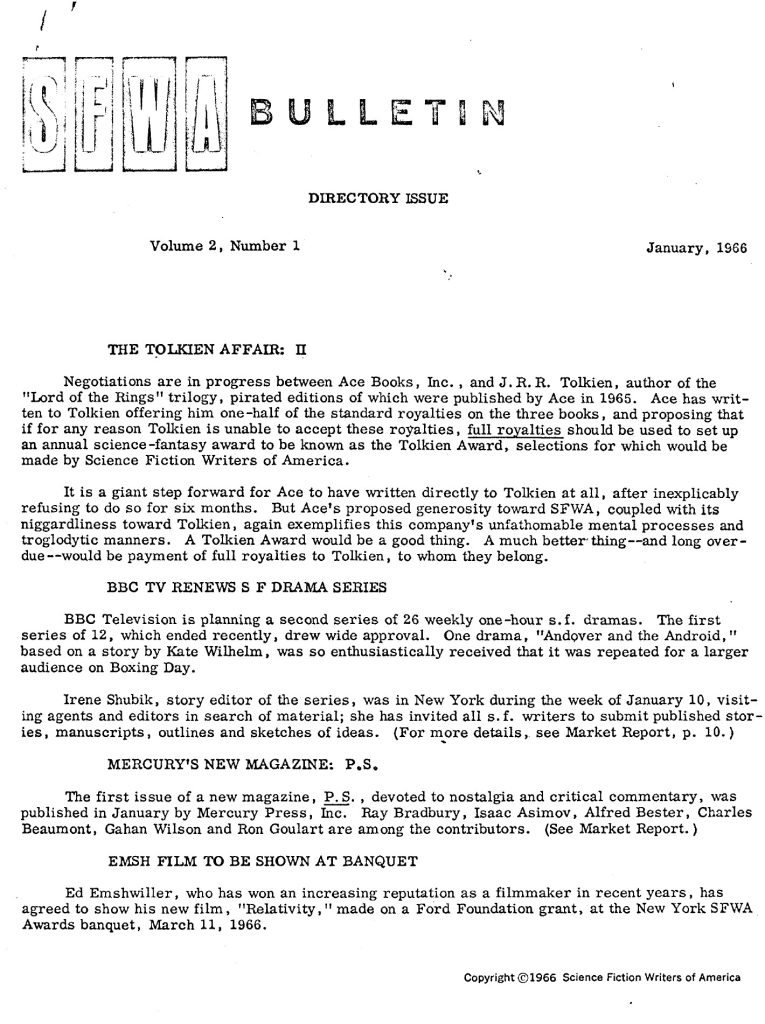

Figure 6. SFWA Bulletin, Volume 2, Number 1. Scanned copy from the collection of Michael Capobianco. January, 1966.

Bulletin issue #4, which came out in January 1966 (Figure 6), noted that negotiations between Ace and Tolkien were underway and that Wollheim was giving Tolkien a choice of either 50 percent standard royalties or 100 percent royalties used to set up an annual science-fantasy “Tolkien Award” with winners to be selected by SFWA. By the following April issue, Ace had paid full royalties “in excess of $9,000” to Professor Tolkien and agreed to stop printing new copies of the trilogy.

The question most pertinent to this history immediately arises: How much did SFWA have to do with this victory? Tolkien’s official biography attributes the change in Ace’s policies to “considerable pressure” being applied by SFWA, an “influential body.” While it’s clear that fan pressure and media attention had a great effect on the outcome, there’s no question that SFWA made a difference.

In the January 1966 Bulletin, Knight summarizes the organization’s progress as “hav[ing] weathered our first year well,” with 179 members. He gives special thanks to Lloyd Biggle, Jr. and Judith Ann Lawrence Blish for their work and concludes: “SFWA is here to stay.”

Michael Capobianco is co-author, with William Barton, of the SF books Iris, Alpha Centauri, Fellow Traveler, and White Light. He has published two solo science fiction novels, Burster and Purlieu as well as short fiction. Capobianco was President of SFWA from 1996–1998 and again in 2007–2008. He currently serves as SFWA’s Authors Coalition Commissioner, Chair of SFWA’s Contracts Committee, Co-chair of SFWA’s Legal Affairs and Estates-Legacy Committees, and is a member of SFWA’s History Committee.

Michael Capobianco is co-author, with William Barton, of the SF books Iris, Alpha Centauri, Fellow Traveler, and White Light. He has published two solo science fiction novels, Burster and Purlieu as well as short fiction. Capobianco was President of SFWA from 1996–1998 and again in 2007–2008. He currently serves as SFWA’s Authors Coalition Commissioner, Chair of SFWA’s Contracts Committee, Co-chair of SFWA’s Legal Affairs and Estates-Legacy Committees, and is a member of SFWA’s History Committee.