Inside the Fiction Editor’s Mind: Does the Writer’s Identity Matter?

By Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki

So, does the writer’s identity matter? The short answer is, well, yes.

But the question people mean to ask when they ask if the writer’s identity matters is: should the writer’s identity matter?

Whether something matters or whether it should matter are two very different things. The latter is slightly more complex.

Publishing is a business: the business of providing for readers what to read. The editor is an assistant to the publisher in this endeavour. In the business of publishing, the writer’s identity matters because readers care not just about what they read but who they read. Readers often develop favourites in the writing world and will return again and again to enjoy the words of those favourites. The publisher who wants to cater to their consumers provides what they demand.

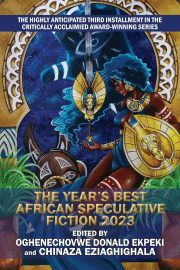

Hence, it is not just the reading material but also the writer that matters to the publisher. The writer’s identity is inseparable from the writer themself, who they are. So, the writer’s identity does matter. It directly influences how many and who reads the material—does the audience trust the pronouncements of a British royal, for example, on the lives of people in former British colonies? A demographic of people who have historically suffered oppression may not want to read work by someone who partook of, or contributed to, said suffering. There have also been reading lists made and propagated to highlight the works of writers from marginalized demographics. We have seen the rise of Year’s Best lists that focus on these marginalized demographics, like the Year’s Best African Speculative Fiction, the first volume of which won the World Fantasy award. Also, We’re Here: The Best Queer Speculative Fiction 2020, which won the Locus award. Works like these have been met with much enthusiasm by the reading public. Wokeness? Or is the publisher simply considering the concerns of their customers?

The more complex questions people often mean to ask are: should the writer’s identity matter? Does it affect the intrinsic value of the piece of writing?

The short answer I gave to this was, “Yes.” The why is a bit longer. It might be an enticing idea on the surface that writing should matter only for the intrinsic value or quality of it, separate from the writer and their identity. But understanding why writing that is art matters will lead us to another question: what is it that gives writing value?

This question will lead us to a view I have often expressed about the deficiency of AI art and what is valuable about stories and writing. One might ask, “What makes a good story?” The answers provided may range from language, to characterization, to plot, to dialogue, to any number of other things. My answer is, none of those things.

It’s not any “thing” that makes a story, any of those techniques or devices, but people. It’s people that make a story good. Readers, critics, and other writers who also happen to be both. That’s why quality in writing is a subjective thing that varies across place and time. People of each place and time coming together to collectively decide if a piece of writing is good invariably makes it so.

So, what makes people decide if a story is good? This is where AI deficiency comes in. People value writing and stories not because of the elements that are said to make them good, but because of how these stories speak to them. How much they can relate to them, how much of themselves they can see in them. This is why a story or piece of writing may lack the things we say have value, but we still love it: a simple piece of writing devoid of complex language, or an overly complex one, etc. If it strikes that nerve, that chord inside us where music thrums, we are taken, owned by that piece of work.

And this is something that AI cannot have: humanity. It can replicate parts of humanity that it has consumed, but it cannot possess or express any itself. It’s that humanity that draws us, that we love in a piece of writing—the person behind it. When we read about love, we know that it was written by a person who has loved or has the capacity to love. So, the suspension of disbelief needed is not too much. Much less than if a thing entirely incapable of love “wrote” that piece of work. Same with hate or whatever other elements of humanity are portrayed in that writing. What we would have from AI is a copy of a copy of a copy of humanity without any from the expressor mixed in. And while we might say humans learn by copying as well, it’s not blind regurgitation, but with their own human experiences mixed in, adding to the work. It’s that combined flavour the reader connects with.

If the humanity of the writer matters and is what speaks most fervently to the reader, does their identity not also matter? Of course, it does.

When we write about an experience from a person who cannot possibly have had that experience, the suspension of disbelief is that much greater, affecting how the writing is received by the reader. Because they understand, even if just subconsciously, that the account is several places removed, researched, or faked. The research has to be that much more thorough, or the writer’s disconnect from the identity is that much more visible.

The writing is thus not something separate from the writer. It carries the writer’s essence, bits and pieces of them in the work. When you read a piece of work, you are reading a piece of the writer. Because the two are inseparable.

Those bits and pieces of the writer, their humanity that seeps into the work, shape it. Define and decide it. The reader knows this and takes it into cognizance on some fundamental level. If I wanted to read, say, an account of how the victims of the Nigeria-Biafra civil war in Southern and Eastern Nigeria survived, would I prefer to hear it from a Northern/Western soldier of the Nigerian army? Even a fictitious account. Does the identity of the writer not matter here, then? Even in fictitious suffering? How trustworthy would an account from the latter be? This is not to say that writing cannot reflect experiences that the writer has not had. However, it does matter what they have; it does affect the writing and work.

The writer’s identity matters on different levels that vary from reader to reader. But they matter. And what matters to the reader matters to the publisher and editor. Because writing is the business of providing for readers.

Our identity is in our language and writing. Culture, mannerisms, experiences, etc., which we carry into the work subconsciously. If bits and pieces of the writer are invariably carried into the work, which they are, doesn’t that mean that cognizance should be given to who writes what? Because those bits and pieces can influence or affect the interpretation of the work. And they should.

How much weight this is given is a different thing, of course, and dependent on the discretion of the editor and publisher of the work. This is why most submissions request a cover letter to come with them, giving some information on the writer.

Something I have noticed as a writer with thousands of submissions under his belt, and who has read for a handful of pro mags and edited several publications, is that even when the work is being read anonymously, the writer’s identity is sought before publication. This calls to mind the August 2023 controversy with the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, where there was an uproar over their acceptance of a work by a fascist, with the story being eventually pulled after the public uproar over the acceptance. Obviously, the reading public and the magazine’s audience care who it reads. It cares about the persona, identity, and reputation of the writer. The reading public cares because it matters who we give that space to, and who takes up that space in publication. This answers the first question very clearly. Does the identity of the writer matter? Yes.

This is also reflected in other ways, like when writers from certain backgrounds write utopic works while living in societies considered dystopic. There are accounts of those works being rejected by editors and publishers. And we all know of the age-old problem of genre snobbery. As a Nigerian writer, I can speak to the fact that many people don’t expect us to write genre fiction or much other than literary fiction that touches on stories of our dark and gory realities. So obviously our identities are factored in. It impacts us negatively and positively. The reading public holds expectations of writers based on their identities. And those expectations influence what they read.

Does it matter? Definitely, yes. Should it matter? Also, yes. It should matter. How much should it matter? That, I’ll say, is dependent on the discretion of the editor and publisher. It is their business after all. As a publisher and editor from a marginalized demographic, being African, continental, and disabled, I strongly believe in giving space and voice to people who have stories to tell that are not oft heard. As Chinua Achebe said, until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.

For a writer, their identity can be a thing that extends entirely beyond the realm of business. So it’s more complex for them than for the editor and publisher. Especially for BIPOC or marginalized writers who have to navigate more nuanced situations with their identity. I will say, though, that there are always editors and publishers willing to consider the nuances of these positions.

So ends my journey in questioning the value of identity in stories and writing. There are many more questions and various answers to them. And we will continue to ask and find more answers as we go.

Author Bio: Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki is an African speculative fiction writer, editor & publisher from Nigeria. He has won the Nebula, Otherwise, Nommo, British & World Fantasy awards and been a finalist in the Hugo, Locus, Sturgeon, British Science Fiction and NAACP Image awards. His works have appeared in Asimov’s, F&SF, Uncanny Magazine, Tordotcom, Galaxy’s Edge, and others. He edited the Bridging Worlds, Year’s Best African Speculative Fiction anthology and co-edited the Dominion, and Africa Risen anthologies. He was a CanCon goh and a guest of honour at the Afrofuturism themed ICFA 44 where he coined a new term/genre label, Afropantheology.

Author Bio: Oghenechovwe Donald Ekpeki is an African speculative fiction writer, editor & publisher from Nigeria. He has won the Nebula, Otherwise, Nommo, British & World Fantasy awards and been a finalist in the Hugo, Locus, Sturgeon, British Science Fiction and NAACP Image awards. His works have appeared in Asimov’s, F&SF, Uncanny Magazine, Tordotcom, Galaxy’s Edge, and others. He edited the Bridging Worlds, Year’s Best African Speculative Fiction anthology and co-edited the Dominion, and Africa Risen anthologies. He was a CanCon goh and a guest of honour at the Afrofuturism themed ICFA 44 where he coined a new term/genre label, Afropantheology.