A Brief History of Persian Sci-Fi

By Kamiab Ghorbanpour

For many years in Iran, and Persian pop culture in general, science-fiction books, movies, and TV shows were often ridiculed as “testicles-fiction” (تخمی “testicles” and تخیلی “fiction” have a similar stress).

This wasn’t always the case, though. During the new wave of science fiction in the ’60s and ’70s, books and shows like Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series and Star Trek: The Original Series reached Iranian audiences and were welcomed with open arms by the middle class. The term “Spuki” (Spock-like) even became a common phrase in the late years of the Imperial State of Iran to describe people who looked or acted like Mr. Spock.

Unfortunately, very little science-fiction or fantasy content was produced at the time by Iranians themselves. The high level of censorship, banned books, and general state monitoring didn’t let people get creative in related cultural fields. After the Iranian Revolution (later known as the Islamic Revolution), things got even worse. A series of cultural purges took place all over the country for almost a decade, called the Cultural Revolution. The likes of Asimov’s books and Star Trek shows were seen as either inappropriate or Western propaganda.

Things began to change slowly at the start of the 21st century when fantasy novels such as The Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter, and Deltora Quest found their way to the Iranian market. This massive importation of the fantasy genre changed people’s attitudes, and today you can find numerous adults in their 20s or 30s who grew up with the genre. Perhaps due to Iran’s own cultural identity being inextricably linked to its mythology and many fantastical and heroic stories, people were more accepting of fantasy. At least, that was what genre publications told themselves.

The Ghasemkhani Brothers

The 2000s was also the golden age of sitcoms in Iran, and two names became quite well-known: Mehrab and Payman Ghasemkhani. These brothers wrote for some of the most memorable shows of the era, such as The Dots and Barareh Nights. The Ghasemkhani brothers are massive science-fiction geeks, and their passion for the genre can be seen even in their earliest work. In Pavarchin, the show that made them famous, one character is a carefree nerd who constantly references Star Wars: something that was, at the time, quite alien to the majority of Iranians.

They continued to squeeze their love of science fiction into different sitcoms. Sometimes they simply named characters and objects after famous franchises, and sometimes they created parodies of beloved stories from other contexts. It wasn’t until 2009 that they finally found the opportunity to create their own science fiction sitcom show, called The Travelers.

The Travelers uses a format familiar to Iranian sitcoms: a dichotomous relationship between people who are coming from outside (usually the countryside) to modern Tehran. But instead of coming from the countryside, this core family is made up of aliens from another planet: sent on a secretive mission and having to adapt to Earth, specifically Iranian society. (Westerners might recall a similar premise in 3rd Rock from the Sun.) These “travelers” are often surprised by Persian culture, societal norms, and political structures. For example, the mind-bogglingly corrupt and bureaucratic nature of paperwork makes even the strongest officer among them frustrated, while the repetitive nature of student homework is seen as a form of torture, not education. The honest and funny criticisms of Iranian society using a science-fiction premise turned The Travelers into a hit TV show.

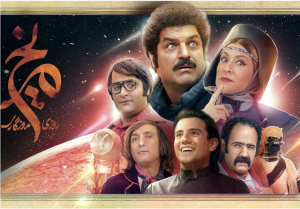

The cover of Once Upon a Time Mars./ Credit: gemtvseries.tv

After working on numerous hit shows and movies, the Ghasemkhani brothers were again given control over a show in 2022, and turned it into their passion project. Once Upon a Time Mars is a sequel to The Travelers, but this time it takes place on Mars, and with a much bigger budget. Mehrab Ghasemkhani (the creator) is known for having strong political stances, which means that Once Upon a Time Mars is also filled with political and social commentaries. One great example is that the society on Mars is completely matriarchal, unlike Iran. Although the matriarchy in the show is comedic, it holds up a mirror to the reality for many Iranians.

A Bright Future?

Despite the Ghasemkhani brothers’ efforts, science fiction is still very niche in Persian pop culture. However, the literature is more promising. In 2004, a group of young people who loved fantasy and science fiction started a website called Fantasy Academy, where they published books, stories, and articles to familiarize Iranian society with the genres. Their success is evident both in their survival and what they have achieved. Many who were part of this campaign have now translated great literary works such as Frank Herbert’s Dune and Isaac Asimov’s novels.

Many have also produced their own creative universes–such as Muhammad R. Idrum, whose Mavara won at Nufe, a new festival celebrating domestic science fiction and fantasy literature, along with Mahdi Bonvari, Zahi Kazemi, and Fariba Kalhor: other writers of Persia’s latest science-fiction era.

Mavara advertisement on an online book shop./ Credit: Taaghche

Fantasy Academy continues its work as the Speculative Fiction Group, or SFG, at 3feed.ir, but today they are far from being the only genre enthusiasts in Iran. Despite heavy censorship and general hardship, many write science fiction and fantasy books, articles, and stories. Hopefully, the current political climate will change for the better, because with freedom of the press will come much more creativity and room for growth–something that Iranian writers and creators have been dying for in spirit, and many Iranians are now dying for in practice.

The cover of Zaman-Savar [Time Driver] by Zahi Kazemi: one of a few new series that will hopefully continue to advance Persian SF. /Credit: Ketab Sara-e Tandis.

Kamiab Ghorbanpour is an Iranian-born game designer, researcher, writer, and journalist from Sweden.

Kamiab Ghorbanpour is an Iranian-born game designer, researcher, writer, and journalist from Sweden.