All Time Favorite

by Dennis Mathis

My favorite science fiction story of all time is…

My favorite science fiction story of all time is…

And one of the Borgesian wonders of this mind-bending little short story is that I never remember what the title is or who wrote it, as if one possibility is that I imagined it word by word and it just exists in my head.

But it’s real. It’s here on my bookshelves somewhere, I’m certain, and I’m closing in on it. I’m determined to find it and tell you about it.

The end of the year, this year, has been about shedding books and refining what we have left. The house has gotten too full of them. Dread of the tax-filing season focuses my mind on minuscule Turbotax charitable deductions, and there’s that generosity nudge about Christmas, so I’m at this moment waiting for a truck to arrive from a nonprofit that’s willing to haul away 177 of our books and give us a receipt.

I hope my all-time favorite science fiction story isn’t in there somewhere. It would be a shame to lose it.

I don’t know who these people with the truck are. My wife has made the arrangements. She sent me a message an hour ago:

Did the thrifty people show up?

Let me know when it’s taken care of

Luv

Barbara

Sent from my iPhone

No. Not yet, my love.

My wife deeply wants to get rid of her mother’s bookcases that have become a psychological burden and a drawback in selling the house if it comes to that. The three bookcases are now waiting outside our front door, and there’s a storm coming in from the Pacific. The bookcases are dark and heavy and not especially well made, but Barbara’s mother had good taste and was, as a single mother in the 1960s, very practical, a quality I always admired in her.

It has been maybe two years since Barbara’s mother died, I think. When she moved in with us and we’d had to absorb her belongings into the house, I made an executive decision to keep the bookcases, even though Barbara had hated them since childhood. It caused some friction, but her mother had a lot of books about exercise and arthritis and crossword puzzle dictionaries, and I had seen how these women tended to ignore clutter until a man tries to touch anything. I installed the bookcases, earthquake-proof, in the dark room where Barbara likes to watch television and pet the cats, and they’ve been there ever since, generating resentment.

To get rid of the bookshelves, first we had to get rid of eighteen linear feet of books. Now I’m having donor’s remorse.

The books about last-resort exercise regimens are going today, finally. Books about Oliver Wendell Holmes, Minnesota geology, Finlander socialists who emigrated to the Soviet Union, and a Bible with some writing in the margins are being saved.

Our own books had gotten mixed in, so there’s Barbara’s college Spanish and medical-records textbooks and my half-shelf of books about religion. They need to be relocated somewhere, which entails thinning out all the other bookshelves in the house.

It’s difficult to explain why a person chooses to keep a book they’ll never read again, or for the first time. Out of respect, I cannot get rid of my Upanishads or King James Bible paperbacks, though I dread the day either might come in handy. And, who knows, the Kama Sutra might yield new meanings now I’m past sixty.

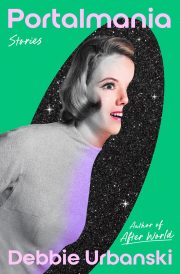

Ah, here it is. My all-time favorite science fiction story, at the bottom of a paper shopping bag, inside a weighty anthology edited — no, “compiled” it says, a good word choice — by Robert Silverberg. Within a pile within a pile within a pile.

This isn’t where I read the story originally, of course, when I was twelve or thirteen. That was some school library. I bought this anthology purely for this one story, though, wow, now that I look at it, every other sci-fi great is in here. I could have sworn my all-time-favorite story wasn’t in table of contents the first two times I looked. I’ll have to keep this.

My all-time favorite science fiction story turns out to be “The Gostak and the Doshes,” by Miles J. Breuer. A title and author designed to leave no trace in a person’s memory.

The hero of the story, a mathematician working at a university, has no name at all. He’s in the office of a colleague named Woleshensky, who’s explaining his latest amusing breakthrough in Relativity Theory, which Woleshensky has already confirmed experimentally.

Just as Einstein forced us to see our surroundings in a radical new way by unifying the x-y-z dimensions of space with the t dimension of time (Woleshensky explains), he himself has been advancing science with his own thought experiments by re-perceiving physical reality with the z and t dimensions swapped. Why not? The math doesn’t care, and it turns out it’s simply our own habits of perception, as biological beings, that prevent us from moving though the world (or “translating,” as Woleshensky prefers to refer to it, since motion is a relativistic concept) with one or more dimensions rotated.

The gobstruck nameless mathematician insists on a demonstration, and Woleshensky obligingly tells him how to do the experiment himself. It just so happens there’s a tree-lined path, leading down from the hilltop building they’re in now, where the angles of the sight lines make it easy to mentally rotate the world. All you have to do is tell yourself you’re walking uphill instead of downhill.

The nameless man tries this out, telling himself he’s walking up the path instead of down. Looking back over his shoulder, he’s perplexed to realize Morton Hall really does seem to be below him… and now it’s an old Gothic Revival building, not the gleaming modernist Morton Hall he’d just left. As he walks through campus, the students all seem remarkably friendly and polite, but everything is slightly askew somehow. Disoriented, he finds his way back to Woleshensky’s office, but there’s a Professor Vibens occupying it now, and Vibens has no idea what the nameless man is talking about…

Ah, the thrifty people have arrived. It’s a beefy man in a black t-shirt and long shorts and significant training shoes. He would look alien to Miles J. Breuer, I think.

He loads the bookcases upright into the back of his pickup, a mighty Ford. Now I know why people drive those things.

I hope he knows what he’s doing, the bookcases makes a towering load. All the boxes and bags of books barely fill half of the remaining truck-bed space. I hope he’s not going out on the freeway. What am I saying? This is California.

I shut the garage door as I watch him rocket into the street. I glance down, and our driveway wants to swallow me up.

—

I went through most of my adult life, until I happened on this Silverberg anthology, not remembering the last half of my all-time-favorite story, so I’ll leave the rest of it — why everyone in this alternate universe is so upset that the gostak distims the doshes, and whether the nameless man will ever get home — for you to find out on your own, if you’re interested.

I’ve always been satisfied with the story’s set-up. I’ve spent a good part of my life trying to convince myself I’m ascending when I’m going down, just to see what happens. It comforts me to think I could someday walk a tree-lined path and slip into another dimension.

Now I have the book with my all-time favorite story. The thrifty people didn’t take it away. Here it is, on my desk. I’ll hold onto it from now on.

I notify Barbara it’s been taken care of, and that I’d rescued her two books (101 Things To Do with Ground Beef and the economically titled Chicken) that on second thought she wanted to give a coworker who moved out of her parents’ home last month and needs to learn how to cook. I tell Barbara the thrift shop’s receipt (a single checkmark beside “furniture”) says it’s an animal rescue organization. That makes her happy.

The house looks more spacious now. Barbara is relieved. She asks if I deposited the check that came in my sister’s Christmas card. My sister always sends enough for airfare, though it never goes for that.

No, I haven’t deposited the check. Come to think of it, where is it? I saw it last on the counter.

I hope it didn’t get into one of those books.

FOOTNOTE —

Miles J. Breuer was a physician who practiced in Lincoln, Nebraska. He wrote dozens of short stories, but only one novel. “Gostak” was published in 1930. Which might mean it was written a year or two earlier. That would be just after the Solvay Conference of 1927, where Einstein was left behind and we advanced into Niels Bohr’s suspension of disbelief about the paradoxes of quantum reality, where we live now. Miles Breuer died just after the war, at the age of 59, after the A-bomb but before the H-bomb.

Dr. Breuer seems to have been a well informed man. The double-talk about gostaks distimming doshes is borrowed from The Meaning of Meaning, a 1923 milestone in logical positivist philosophy. Breuer’s explanation of relativistic frames of reference is concise and instructional in a lively way, and accurate to science as far as I know. As a fiction writer, he doesn’t try our patience too badly. Rather than wanting to edit-down his exposition, I find myself wanting to quote it:

Sir Isaac Newton tried in his mathematics to express a universe as though beheld by an infinitely removed and perfectly fixed observer. Mathematicians since his time, realizing the futility of such an effort, have taken into consideration that what things “are” depends upon the person who is looking at them.

•••

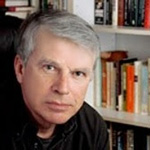

Dennis Mathis once had a bright future as a novelist, but he got distracted by computer systems. He threw away his unfinished first novel in 1984 and spent the next twenty years in publishing production and corporate communications. In 1994 he created a Fortune-20 corporation’s first public website, and for the next decade developed digital media and database systems for numerous high-tech startups.