Stephen Baxter: My Favorite Robert Silverberg Novel

In my mind SFWA has always been associated with Robert Silverberg.

In my mind SFWA has always been associated with Robert Silverberg.

Bob was of course the second president of the organisation, and he introduced my young mind to the very conception of SFWA through his editing of the first of the1960s ‘Hall of Fame’ anthologies. My understanding now is that this project was Silverberg’s inspiration, to help get the still-young organisation on a sounder financial footing. So the first impression of SFWA I got, reading UK reprints in the 1970s when I was in my teens, was of a great writer, generously presenting stuff by other great writers, in aid of an organisation dedicated to the support of others in the field. What’s not to love about that?

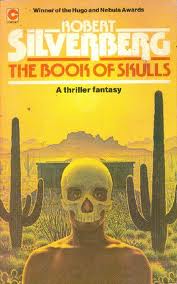

Pass on a few more years and my appreciation of Silverberg’s own work grew. But it was only relatively recently – well, at my age ten years ago is relatively recent – that I came to what’s become possibly my favorite of Bob’s books, The Book of Skulls. And not long after reading it I met Bob, not for the first time, at some event or other, and we talked about the book. So that seems to me an eminently suitable subject for this blog entry.

The elevator pitch: Four American college boys seek out a secretive desert sect with an extraordinary promise – immortality, but for only two of them: ‘Eternal life…An existential gamble. Two to live forever, two to die’. The pressure of this dreadful bargain tears the boys apart.

The Book of Skulls was first published in 1971. Silverberg was 36. Having established himself as a master of genre science fiction – his first sf novel was published in 1955 – he was in the middle of a remarkable eight-year period of creative experimentation, in which the material, the ideas, the artistry, seemed to be his drivers, rather than genre forms. Silverberg told me of Skulls, ‘I never consciously thought of the book as being a horror novel, or sf, or fantasy. I had a story to tell, inspired by a reproduction I saw of a medieval manuscript page bearing a row of skulls (it was used on the US hardcover edition), and the category it might fall into was not anything I spent time considering …I also had set a technical challenge for myself – to tell the story through four different first-person narrators.’

Those narrators are carefully constructed. All American, all aged roughly 20, the four boys are polarized types, ethnically, sexually, intellectually. A hint of Silverberg’s inspiration, perhaps, is contained in a reference to ‘an ethnographical film about some African bushmen out hunting a giraffe [which] drew a structural metaphor of [their] society’. Similarly, here is a metaphor of American society in a story of four college kids out pursuing a dream (or a nightmare). You have a Shaman in Eli the bookish New York Jew, a Headman in Timothy the spoiled preppy rich kid from Chicago, a Clown in Ned the overtly homosexual Boston-Irish Catholic, and a Beautiful One in Oliver the repressed Kansas farm boy.

To approach their goal the boys must first endure a long drive into the heart of a desert that seems alien to them all. The strangeness of their quest is contrasted with the mundane surfaces of their lives: they start out treating it as a game – but what if it isn’t? And the stress has been mounting since even before they left Manhattan.

When they do find their monastery, populated by ageless, leathery-skinned ‘fraters’, Silverberg makes the immortality project utterly convincing. Science fiction writers are practiced in making the impossible seem plausible. So there are references to the familiar, and distracting details, and irresistible hints of secret roots going back all the way to the Ice Age: ‘You have come to us out of Altamira, out of Lascaux, out of doomed Atlantis itself’. It’s all smoke and mirrors, of course; you don’t really see anything, but you’re left feeling that you do.

But all the while the approaching crux of the boys’ quest ratchets up the psychological pressure: ‘This frightens me. I’m likely to find out something about myself I don’t want to know’. The trick of four first-person narrators works beautifully. The characters’ outer layers and inner levels are built up in intense detail; on one level this is a parable of how little we know each other, how alone we humans are. And through long, fluent first-person passages you are locked firmly into the heads of the four narrators and drawn into their conflicts inner and outer, until the final disintegration overwhelms.

On still another level the book captures its moment in time. The late 1960s was an age of intense psychological (some of it drug-fueled) experimentation, of self-awareness, of a restless search for something new and spiritual. Perhaps Silverberg can be criticized that his four 20-year-olds are a little too knowing, of themselves and their position in time. But they are archetypes of an age which survives in the imagination, so enduring has 1960s culture proven to be, demonized or eulogized in turn.

When I first read the book I was deeply impressed with its technical quality, but it was the sheer intensity of the prose that really hooked me. I read it in a sitting, and it reads as though it was written that way. Silverberg himself may not have defined this as a horror novel. But at its deepest core the book is an extended meditation on the ultimate horror, the inevitability of personal death in an immense and ancient universe. And it is a story of personal disintegration brought about purely through psychological pressure, with nary a special effect in sight. It foreshadows ‘The Blair Witch Project,’ perhaps – and surely it would make a great movie.

When I first read the book I was deeply impressed with its technical quality, but it was the sheer intensity of the prose that really hooked me. I read it in a sitting, and it reads as though it was written that way. Silverberg himself may not have defined this as a horror novel. But at its deepest core the book is an extended meditation on the ultimate horror, the inevitability of personal death in an immense and ancient universe. And it is a story of personal disintegration brought about purely through psychological pressure, with nary a special effect in sight. It foreshadows ‘The Blair Witch Project,’ perhaps – and surely it would make a great movie.

The Book of Skulls is a technical tour de force, deeply unsettling, astounding. Read it in a sitting, as I did; you’ll remember it for a lifetime.

Born in Liverpool, England, in 1957, Stephen Baxter now makes his home in Northumberland. Since 1987 he has published somewhere over forty books, mostly science fiction novels, and over a hundred short stories. Additionally, Baxter has degrees in mathematics, from Cambridge University, engineering, from Southampton University, and in business administration, from Henley Management College. He has taught math and physics, and for several years in information technology. He is a Chartered Engineer and Fellow of the British Interplanetary Society. His science fiction novels have been published in the UK, the US, and in many other countries including Germany, Japan, France. Baxter’s works have won several awards including the Philip K Dick Award, the John W Campbell Memorial Award, the British Science Fiction Association Award, the Kurd Lasswitz Award (Germany) and the Seiun Award (Japan) and have been nominated for several others, including the Arthur C Clarke Award, the Hugo Award and Locus awards.