Guest Post: Writers and Their Literary Estates: Story Reprints

by Jeff VanderMeer

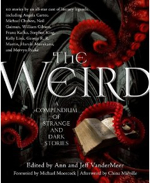

Since the early 1990s, my wife Ann and I have edited or co-edited more than sixteen anthologies containing somewhere shy of three millions words of fiction. Some of those anthologies have collected original fiction, but about half have been reprint anthologies, including the massive 750,000-word The Weird, our most recent effort. Based on these projects, we would suggest that writers think carefully about their wills and their literary estates. This same thought should apply to representation while living, if the writer does not directly control reprint rights to stories, or is not the person an anthologist must contact to acquire those rights. The following thoughts are also offered in the context that about 75 percent of the time, negotiations are conducted in a professional and timely manner.

Since the early 1990s, my wife Ann and I have edited or co-edited more than sixteen anthologies containing somewhere shy of three millions words of fiction. Some of those anthologies have collected original fiction, but about half have been reprint anthologies, including the massive 750,000-word The Weird, our most recent effort. Based on these projects, we would suggest that writers think carefully about their wills and their literary estates. This same thought should apply to representation while living, if the writer does not directly control reprint rights to stories, or is not the person an anthologist must contact to acquire those rights. The following thoughts are also offered in the context that about 75 percent of the time, negotiations are conducted in a professional and timely manner.

***

One way in which writers gain more exposure is by being reprinted in anthologies, or reprinted in magazines. In the case of cult writers, sometimes limited edition reprint collections are also a way to keep someone’s work alive. Writers who do not take the time to create a will with provisions for the handling of their literary estate may help make their work more obscure than it should be, and deprive readers of great fiction for reasons unrelated to an anthologist’s or editor’s desire to include them.

To a least some extent, the ease with which an anthologist can contact a writer’s representative and obtain rights to a story speaks to how often that writer will be reprinted. A nonresponsive agent, publisher, or literary estate is just one of an anthologist’s worries. Another is, believe it or not, active hostility toward the request. A third is a mis-understanding of the marketplace wherein a writer’s representative asks for such an exorbitant fee that the anthologist cannot reprint the story, or a desire to treat the rights as if they were shares in a company, and to not allow any reprinting, hoping the value goes up. A fourth problem is, to be blunt, such inadvertent incompetence that a deal cannot be struck. A fifth problem in the modern era is simply a mis-understanding about what e-book rights mean. These are very simple situations, while others, like family members squabbling over who represents the rights, can be an entirely more complicated scenario.

If reprint rights are difficult to get, for whatever reason, including requiring undue time and effort to negotiate, a writer’s legacy may suffer over time, especially for those writers who specialized in short stories and/or were midlist or indie-press during their lifetimes. If it is hard to find out who holds the rights, this also creates a barrier to reprinting material. (Note that we are not suggesting that anthologists should be given stories for nothing, nor do we believe a writer’s legacy depends solely on these kinds of reprints.)

Because no one can predict who will gain or flag in popularity over time, the upshot is that no matter how little-known you are—perhaps even because you are little-known—you need a will that clearly sets out who will handle your literary estate and how that estate should operate.

Neil Gaiman has some great thoughts about wills here, to which we would just append the following observations. (Gaiman’s people, as you might expect, are awesome to deal with on reprints.)

—Make sure you designate a clear chain-of-command. Include contingency plans in case your first choice passes away.

—Choose individuals to represent you who are business-competent and computer savvy, but who also love books and agree with your ideas about your legacy.

—Make your desires as to how requests for reprints should be handled crystal-clear.

—When negotiating contracts for short story collections, retain your right to permit reprint of individual stories so that you can control exactly how easy (or difficult, if that is your wont) it is for stories to be reprinted.

—Consider allowing your work to be reprinted for free after a limited period, like 40 years, as opposed to the current 70 years.

As you can imagine, all of this is also important with regard to novel-length fiction, especially in cases where a writer’s existing publisher allows titles to fall out of print some time after a writer’s death. Of course, a writer cannot predict every scenario, but having a good plan in place can help immeasurably. Some writers even set up literary corporations while alive, in part to deal with these issues.

Finally, thanks to all of those wonderful writers, agents, estates, and publishers who help make this advice pointed toward exceptions to the rule.

•••

Jeff VanderMeer has had novels published in fifteen languages, won multiple awards, and made the best-of-year lists of Publishers Weekly, the San Francisco Chronicle, the LA Weekly, and many others. His award-winning short fiction has been featured on Wired.com’s GeekDad and Tor.com, as well as in many anthologies and magazines, including Conjunctions, Black Clock, and in American Fantastic Tales (Library of America). His nonfiction has appeared in the New York Times Book Review, the Washington Post, The Huffington Post, the Los Angeles Times, and Salon.com.

Jeff VanderMeer has had novels published in fifteen languages, won multiple awards, and made the best-of-year lists of Publishers Weekly, the San Francisco Chronicle, the LA Weekly, and many others. His award-winning short fiction has been featured on Wired.com’s GeekDad and Tor.com, as well as in many anthologies and magazines, including Conjunctions, Black Clock, and in American Fantastic Tales (Library of America). His nonfiction has appeared in the New York Times Book Review, the Washington Post, The Huffington Post, the Los Angeles Times, and Salon.com.

With his wife Ann, he launched WeirdFictionReview.com, which has become one of the world’s most robust sources for fiction and nonfiction related to the weird. Their latest offering is The Weird, a 750,000-word anthology covering 100 years of weird fiction.

This post first appeared on Jeff VanderMeer’s blog, Ecstatic Days. Photo by Keyan Bowes.

•••

NOTE: SFWA has assembled, and is maintaining, a database of the estates of deceased authors which includes contact information for their heirs and/or agents. This resource enables editors, publishers and agents to seek permissions, make payments and double-check rights.

To see how you can help, please visit our information page. -Editor