by Kelly Barnhill

My father gave me a copy of Julia Child’s letters (As Always, Julia), and, as always, that woman is a revelation. I remember watching her show as a little kid and, after being first entranced by her voice and by all the cool stuff in her kitchen, I remember being struck by her relationship with food. That combination of exasperation and delight, that careless tenderness combined with a firm belief in the democratization of pleasure.

My father gave me a copy of Julia Child’s letters (As Always, Julia), and, as always, that woman is a revelation. I remember watching her show as a little kid and, after being first entranced by her voice and by all the cool stuff in her kitchen, I remember being struck by her relationship with food. That combination of exasperation and delight, that careless tenderness combined with a firm belief in the democratization of pleasure.

That woman loved food. She love the fact that the food she made existed solely to spoon into another person’s mouth. She loved the communal nature of a meal, the shared experience, the moment of delight and euphoria and grace. And she rocked, that woman. She rocked.

The woman who said, “A few drops of Cognac never hurt anything. Neither did a bottle.”

And, “Cooking is like love: it should be entered into with wild abandon, or not at all.”

And, “How can a nation be called great if its bread tastes like kleenex?”

And, “The only time to eat diet food is when you’re waiting for the steak to cook.”

And, “If you’re afraid of butter, use cream.”

And, “Life itself is the proper binge.”

And, “You could use skim milk, of course, but I don’t know why you would.”

This is the woman who taught me to make omelettes for 300 (a skill I use all the time, though for five instead of three hundred).

I love that woman. I love her forever. And I love that my kids have gotten into the habit of watching bits of her show on youtube.

Now, I know – I know for sure – that Julia, if she was to visit my kitchen, would likely turn up her nose at the kinds of foods I typically cook. My family is vegetarian – a state of being that she regarded with the utmost suspicion – and in the summer we eat lots and lots of raw foods straight out of the garden. Still, despite the fact that much of what she taught me does not apply to how I cook now, and how I eat now, I have absorbed lesson after lesson of her cooking practice into my writing practice.

Or, more specifically, my revision practice.

I’m in the throes of revision right now. It’s not a happy place necessarily, or an easy place. The process is difficult, painstaking and sometimes a pain in the butt. It requires patience, planning, insistence, and love. It needs a willingness to appreciate the raw materials in its ugliness, in its shyness, in its unstructured state, as well as a willingness to coax it into a place of beauty, into a delight of the eye and ear and tongue and nose, into a thing whose very existence requires it to be shared.

Or, in other words, what Julia did for the roast chicken, I am now attempting to do with my novel. Here is my recipe:

INSTRUCTIONS FOR ROAST NOVEL

1. Prepare your workspace. Wash your hands.

2. Lay out novel. Run your hands along the pages, feeling for cracks, gaps, and bulges. Pay special attention to the eruptions on the skin. Pull out loose hairs. Mind the feathers.

3. Grease your hands (butter works the best, but you may use olive oil if you are concerned about saturated fats). Run your fingers through the words, making sure to massage between the consonants. As with a roast chicken, anomalies will exist – a thickening here, a flaw there. There will be scars, of course – there always are with a thing that is alive. What you’re looking for is signs of illness, mutilation or genetic distress. Third eyes. Extra digits. Teeth in the throat.

This is not to say there is not a market – or indeed an appetite – for a roasted three-headed chicken, or a chicken with a dolphin’s tail, or a chicken with jeweled eyes. Still, it’s best to know such things up front.

4. Take a very sharp knife and a measure of strong twine. Cut away what cannot be eaten. Cut away that which detracts the eye or the tooth or the tongue. Cut away what is not beautiful, or what is too beautiful. Cut until your fingers bleed, or your heart bleeds – whichever is first.

5. Bind what can be bound. Even in this state, your novel is wily and wild. It will slip from your fingers, dance around the room, run out the door. The parts that you cut will become ambulatory too. They will swing from the chandelier and slither up the walls and mess up your bed. They will hide under carpets and in linen closets and will collude with your kids and steal your credit cards. Indeed, they’re doing it all ready.

6. Gather sweet things and salty things and savory things and herbacious things from your garden and your pots and your cupboards and your pockets. Stuff the gap. You are only doing this to flavor the meat. You will remove it all in a minute.

7. Put it in the oven. Walk away. Do nothing. Don’t check it. Don’t fuss over it. Let the novel sit in peace – in the hot dark, in the cloud of its own steam, in the flow of its own juice. Because there is nothing you can do to it anymore.

NOTE: Please take care when you open the oven. It will not behave itself. It will not go willingly to the table. It will knock you down. It will grow arms and legs and feathers and wings. It will fly away. You will only be left with its lingering scent hanging in the house. It will leave you starving.

•••

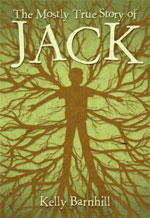

Kelly Barnhill’s short fiction has appeared in Postscripts, Weird Tales, Clarkesworld, Sybil’s Garage and other publications. She also writes high-interest nonfiction books for children. Her first novel, The Mostly True Story Of Jack, is a middle grade fantasy set in rural Iowa about a lonely boy, and an avenging girl, a mysterious house, two possibly murderous cats, a remarkable skateboard, and a rather nasty bit of magic. It appears in bookstores everywhere on August 2, 2011. She is, by all accounts, ridiculously excited about it. She is a former schoolteacher, a former bartender, a former janitor, a former receptionist, a former park ranger, a former wildland firefighter, and a former waitress. The sum of these experiences have prepared her for absolutely nothing — save freelance writing, which she has been happily doing for the past six years. She lives in Minneapolis with her brilliant husband, her three aspiring-evil-genius children, and her emotionally unstable dog.

Kelly Barnhill’s short fiction has appeared in Postscripts, Weird Tales, Clarkesworld, Sybil’s Garage and other publications. She also writes high-interest nonfiction books for children. Her first novel, The Mostly True Story Of Jack, is a middle grade fantasy set in rural Iowa about a lonely boy, and an avenging girl, a mysterious house, two possibly murderous cats, a remarkable skateboard, and a rather nasty bit of magic. It appears in bookstores everywhere on August 2, 2011. She is, by all accounts, ridiculously excited about it. She is a former schoolteacher, a former bartender, a former janitor, a former receptionist, a former park ranger, a former wildland firefighter, and a former waitress. The sum of these experiences have prepared her for absolutely nothing — save freelance writing, which she has been happily doing for the past six years. She lives in Minneapolis with her brilliant husband, her three aspiring-evil-genius children, and her emotionally unstable dog.

This post originally appeared on her blog.